They say the best things in life are free, but we would loudly argue that a dollar can go a long way, too. It all depends on what you do with it. When [lonesoulsurfer] saw this busted-up handheld racing game at the junk store, he fell in love with the lines of the case and gladly forked over a buck in order to give it a new life as a wicked little sound-bending machine with dancing LEDs.

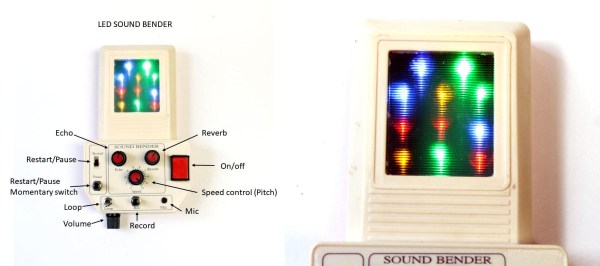

Here’s how it works: [lonesoulsurfer] records a few seconds of whatever into the mic with the looping function switched off, then turns it back on to start the fun. He can vary the pitch with the speed controller pot, or add in some echo and reverb. Once the sound is dialed in, he works the pause button on the left to make melodies by stopping and restarting the loop, or just pausing it momentarily depending on the switch setting.

Here’s how it works: [lonesoulsurfer] records a few seconds of whatever into the mic with the looping function switched off, then turns it back on to start the fun. He can vary the pitch with the speed controller pot, or add in some echo and reverb. Once the sound is dialed in, he works the pause button on the left to make melodies by stopping and restarting the loop, or just pausing it momentarily depending on the switch setting.

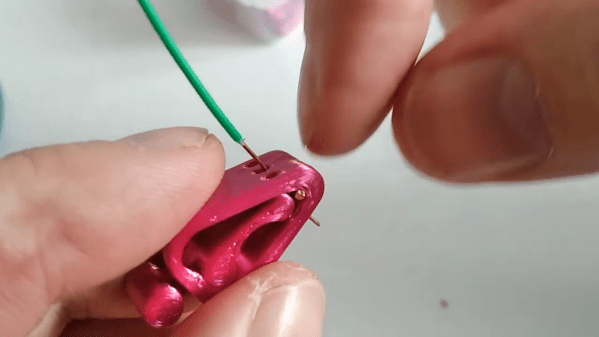

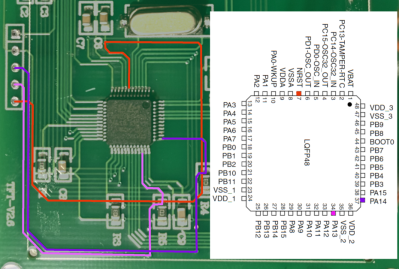

The electronics are a mashup of modules mixed with a custom PCB that combines the recording module with an LM386 amplifier and holds the coolest part of this build — those LEDs that dance to the music behind the toy’s original lenticular screen. Like most of [lonesoulsurfer]’s builds, it’s powered by an old cell phone battery that’s buck-boosted to 5 V. Check out the build and bleep-bloop video after the break.

Lenticular lenses are all kinds of fun. Get one that’s big enough, and you can use it to disappear for a while.

Continue reading “Racing Game Crashes Into Its Next Life As A Sound Bender”