Not content to rule the world of digital watches, Casio also dominated the home musical keyboard market in decades past. If you wanted an instrument to make noises that sounded approximately nothing like what they were supposed to be, you couldn’t go past a Casio. [Marwan] had just such a keyboard, and wanted to use it with their PC, but the low-end instrumented lacked MIDI. Of course, such functionality is but a simple hack away.

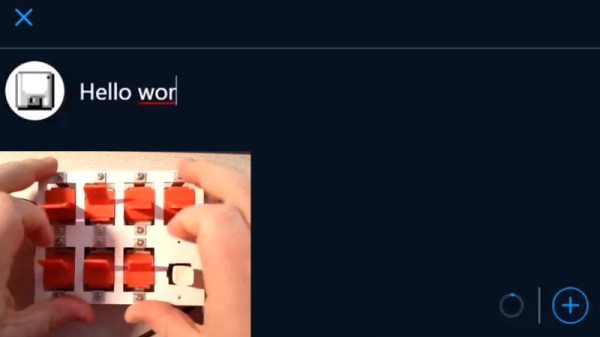

The hack involved opening up the instrument and wiring the original keyboard matrix to the digital inputs of an Arduino Uno. The keys are read as a simple multiplexed array, and with a little work, [Marwan] had the scheme figured out. With the Arduino now capable of detecting keypresses, [Marwan] whipped up some code to turn this into relevant MIDI data. Then, it was simply a case of reprogramming the Arduino Uno’s ATMega 16U2 USB interface chip to act as a USB-MIDI device, and the hack was complete.

Now, featuring a USB-MIDI interface, it’s easy to use the keyboard to play virtual instruments on any modern PC DAW. As it’s a popular standard, it should work with most tablets and smartphones too, if you’re that way inclined. Of course, if you’re more into modular synthesizers, you might want to think about working with CV instead!

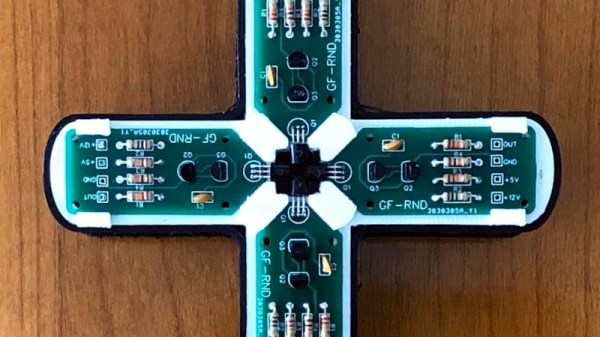

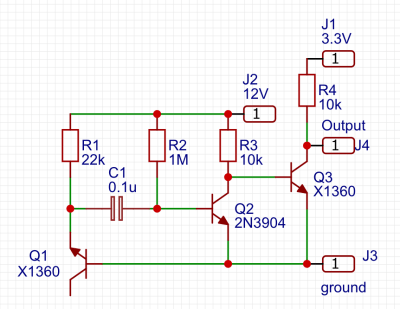

One of the simplest circuits for generating random analogue noise involves a reverse biased diode in either Zener or avalanche breakdown, and it is a variation on this that he’s using. A reverse biased emitter junction of a transistor produces noise which is amplified by another transistor and then converted to a digital on-off stream of ones and zeroes by a third. Instead of a shift register to create his four bits he’s using four identical circuits, with no clock their outputs randomly change state at will.

One of the simplest circuits for generating random analogue noise involves a reverse biased diode in either Zener or avalanche breakdown, and it is a variation on this that he’s using. A reverse biased emitter junction of a transistor produces noise which is amplified by another transistor and then converted to a digital on-off stream of ones and zeroes by a third. Instead of a shift register to create his four bits he’s using four identical circuits, with no clock their outputs randomly change state at will.