OpenWrt announced a problem in opkg, their super-lightweight package manager. OpenWrt’s target hardware, routers, make for an interesting security challenge. A Linux install that fits in just 4 MB of flash memory is a minor miracle in itself, and many compromises had to be made. In this case, we’re interested in the lack of SSL: a 4 MB install just can’t include SSL support. As a result, the package manager can’t rely on HTTPS for secure downloads. Instead, opkg first downloads a pair of files: A list of packages, which contains a SHA256 of each package, and then a second file containing an Ed25519 signature. When an individual package is installed, the SHA256 hash of the downloaded package can be compared with the hash provided in the list of packages.

It’s a valid approach, but there was a bug, discovered by [Guido Vranken], in how opkg reads the hash values from the package list. The leading space triggers some questionable pointer arithmetic, and as a result, opkg believes the SHA256 hash is simply blank. Rather than fail the install, the hash verification is simply skipped. The result? Opkg is vulnerable to a rather simple man in the middle attack.

OpenWrt doesn’t do any automatic installs or automatic updates, so this vulnerability will likely not be widely abused, but it could be used for a targeted attack. An attacker would need to be in a position to MitM the router’s internet connection while software was being installed. Regardless, make sure you’re running the latest OpenWrt release to mitigate this issue. Via Ars Technica.

Wireguard V1.0

With the Linux Kernel version 5.6 being finally released, Wireguard has finally been christened as a stable release. An interesting aside, Google has enabled Wireguard in their Generic Kernel Image (GKI), which may signal more official support for Wireguard VPNs in Android. I’ve also heard reports that one of the larger Android ROM development communities is looking into better system-level Wireguard support as well.

Javascript in Disguise

Javascript makes the web work — and has been a constant thorn in the side of good security. For just an example, remember Samy, the worm that took over Myspace in ’05. That cross-site scripting (XSS) attack used a series of techniques to embed Javascript code in a user’s profile. Whenever that profile page was viewed, the embedded JS code would run, and then replicate itself on the page of whoever had the misfortune of falling into the trap.

Today we have much better protections against XSS attacks, and something like that could never happen again, right? Here’s the thing, for every mitigation like Content-Security-Policy, there is a guy like [theMiddle] who’s coming up with new ways to break it. In this case, he realized that a less-than-perfect CSP could be defeated by encoding Javascript inside a .png, and decoding it to deliver the payload.

Systemd

Ah, systemd. Nothing seems to bring passionate opinions out of the woodwork like a story about it. In this case, it’s a vulnerability found by [Tavis Ormandy] from Google Project Zero. The bug is a race condition, where a cached data structure can be called after it’s already been freed. It’s interesting, because this vulnerability is accessible using DBus, and could potentially be used to get root level access. It was fixed with systemd v220.

Mac Firmware

For those of you running MacOS on Apple hardware, you might want to check your firmware version. Not because there’s a particularly nasty vulnerability in there, but because firmware updates fail silently during OS updates. What’s worse, Apple isn’t publishing release notes, or even acknowledging the most recent firmware version. A crowd-sourced list of the latest firmware versions is available, and you can try to convince your machine to try again, and hope the firmware update works this time.

Anti-Rubber-Ducky

Google recently announced a new security tool, USB Keystroke Injection Protection. I assume the nickname, UKIP, isn’t an intentional reference to British politics. Regardless, this project is intended to help protect against the infamous USB Rubber Ducky attack, by trying to differentiate a real user’s typing cadence, as opposed to a malicious device that types implausibly quickly.

While the project is interesting, there are already examples of how to defeat it that amount to simply running the scripts with slight pauses between keystrokes. Time will tell if UKIP turns into a useful mitigation tool. (Get it?)

SMBGhost

Remember SMBGhost, the new wormable SMB flaw? Well, there is already a detailed explanation and PoC. This particular PoC is a local-only privilege escalation, but a remote code execution attack is like inevitable, so go make sure you’re patched!

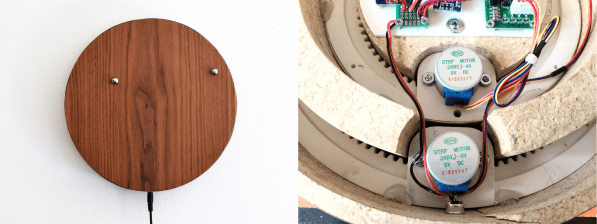

This clock takes design cues from the Story clock, a visual revolution in counting down time which uses magnetic levitation to move a single bearing around the face exactly once over a duration of any length as set by the user. As a clock, it’s not very useful, so there’s a digital readout that still doesn’t justify the $800 price tag.

This clock takes design cues from the Story clock, a visual revolution in counting down time which uses magnetic levitation to move a single bearing around the face exactly once over a duration of any length as set by the user. As a clock, it’s not very useful, so there’s a digital readout that still doesn’t justify the $800 price tag.