After the end of the Second World War the United States and the Soviet Union started working feverishly to perfect the rocket technology that the Germans developed for the V-2 program. This launched the Space Race, which thankfully for everyone involved, ended with boot prints on the Moon instead of craters in Moscow and DC. Since then, global tensions have eased considerably. Today people wait for rocket launches with excitement rather than fear.

That being said, it would be naive to think that the military isn’t still interested in pushing the state-of-the-art forward. Even in times of relative peace, there’s a need for defensive weapons and reconnaissance. Which is exactly why the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) has been soliciting companies to develop a small and inexpensive launch vehicle that can put lightweight payloads into Earth orbit on very short notice. After all, you never know when a precisely placed spy satellite can make the difference between a simple misunderstanding and all-out nuclear war.

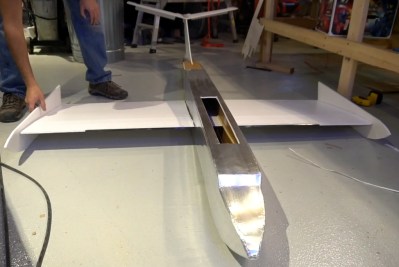

More than 50 companies originally took up DARPA’s “Launch Challenge”, but only a handful made it through to the final selection. Virgin Orbit entered their air-launched booster into the competition, but ended up dropping out of contention to focus on getting ready for commercial operations. Vector Launch entered their sleek 12 meter long rocket into the competition, but despite a successful sub-orbital test flight of the booster, the company ended up going bankrupt at the end of 2019. In the end, the field was whittled down to just a single competitor: a relatively unknown Silicon Valley company named Astra.

Should the company accomplish all of the goals outlined by DARPA, including launching two rockets in quick succession from different launch pads, Astra stands to win a total of $12 million; money which will no doubt help the company get their booster ready to enter commercial service. Rumored to be one of the cheapest orbital rockets ever built and small enough to fit inside of a shipping container, it should prove to be an interesting addition to the highly competitive “smallsat” launcher market.