Here’s a simple and interesting idea that increases the visual persistence of a laser scanner image. Using glow-in-the-dark paint, [Daito Manabe] prepares a surface so that the intense light of a laser leaves a trace that fades slowly over time. He’s using the idea to print monochromatic images onto the treated surface, starting with the darkest areas and ending with the lightest. The effect is quite interesting, as the image starts out seeming quite abstract but reveals its self with more detail over time.

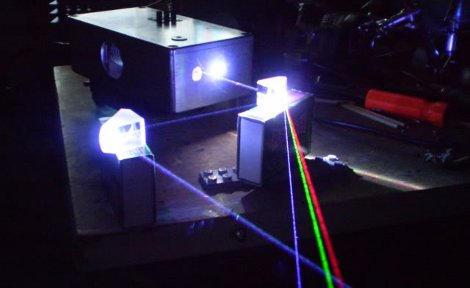

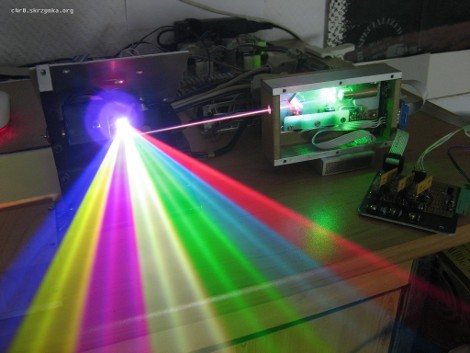

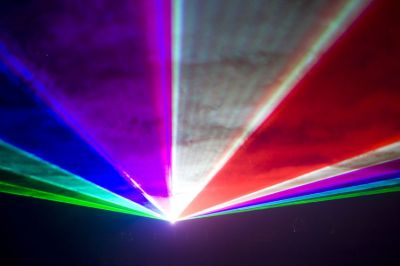

As evidenced in the test videos, the bursts of laser scanning are matched to the fade rate of the paint. Therefore it would seem that the time taken to “write” an image is directly proportional to the desired visual persistence of the final image. We wonder, by combining clever timing and variable laser intensity could you write images much more quickly? How hard would it be to use this for moving pictures? With the ability to create your own tiny laser projector, and even an RGB scanner, there must be a lot of potential in this idea for mind-blowing visual effects. Add portability by using a phosphor-treated projection screen!

Share your ideas and check out the test videos after the break.