Regular Hackaday readers may recall that a little less than a year ago, I had the opportunity to explore a shuttered Toys “R” Us before the new owners gutted the building. Despite playing host to the customary fixture liquidation sale that takes place during the last death throes of such an establishment, this particular location was notable because of how much stuff was left behind. It was now the responsibility of the new owners to deal with all the detritus of a failed retail giant, from the security camera DVRs and point of sale systems to the boxes of employee medical records tucked away in a back office.

The resulting article and accompanying YouTube video were quite popular, and the revelation that employee information including copies of social security cards and driver’s licenses were left behind even secured Hackaday and yours truly a mention in the New York Post. As a result of the media attention, it was revealed that the management teams of several other stores were similarly derelict in their duty to properly dispose of Toys “R” Us equipment and documents.

Ironically, I too have been somewhat derelict in my duty to the good readers of Hackaday. I liberated several carloads worth of equipment from Geoffrey’s fallen castle with every intention of doing a series of teardowns on them, but it’s been nine months and I’ve got nothing to show for it. You could have a baby in that amount of time. Which, incidentally, I did. Perhaps that accounts for the reshuffling of priorities, but I don’t want to make excuses. You deserve better than that.

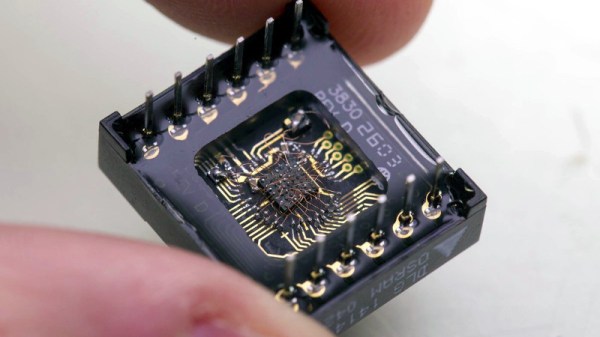

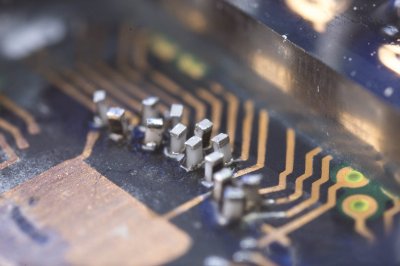

So without further ado, I present the first piece of hardware from my Toys “R” Us expedition: the VeriFone MX 925CTLS. This is a fairly modern payment terminal with all the bells and whistles you’d expect, such as support for NFC and EMV chip cards. There’s a good chance that you’ve seen one of these, or at least something very similar, while checking out at a retail chain. So if you’ve ever wondered what’s inside that machine that was swallowing up your debit card, let’s find out.

Continue reading “Teardown: VeriFone MX 925CTLS Payment Terminal”