For many, the Thinkpad T25 was something of a dream come true. Celebrating the 25th anniversary of the venerable business-oriented laptop that hackers love so much, it featured a design inspired by “retro” Thinkpads of yore, but with modern hardware inside. Unfortunately, as it was more fan service than a serious revitalization of classic Thinkpad design, the T25 was only ever available in a single hardware configuration.

[kitsunyan] liked the look and feel of the T25, but in 2019 was already feeling a bit let down by the hardware. The screen wasn’t up to snuff, and while the CPU is an i7, it only has dual cores. To make sure the T25 is still viable down the road, it seemed the only option was to try to transplant the hardware from one of the current Thinkpad models into the anniversary chassis. It certainly wasn’t easy, but given the fact that the T25 was more of a redress than a completely new product to begin with, everything came together a lot better than you might expect.

To help put things into perspective, the T25 is basically a modified version of the T470. Last year, Lenovo replaced the T470 with the new T480 that has just the sort of hardware improvements that [kitsunyan] wanted. The T480 was more of a refresh than a complete revamp, so the actual chassis of the machine didn’t change much compared with its predecessor. That being the case, it seemed like it should be possible to transplant the newer T480 components into the T470 derived T25. Got all that straight?

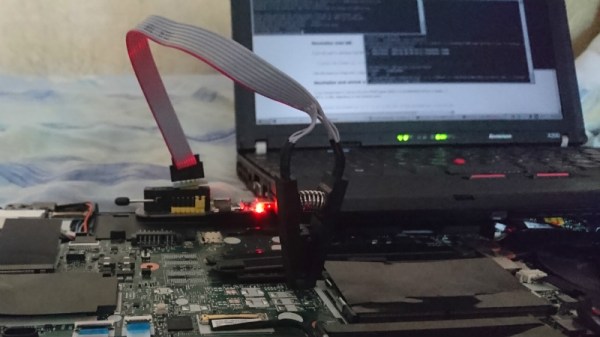

[kitsunyan] was able to put this theory to the test when the opportunity to connect a T25 keyboard to the newer T480 presented itself. Since the 7-row keyboard on the anniversary edition was one of its biggest selling points, seeing if it would work on another machine was kind of a big deal. It didn’t fit physically, and some of the keys didn’t work as expected, but it at least had the same connector and didn’t let out the magic smoke. It represented the first tiny step of a much larger journey.

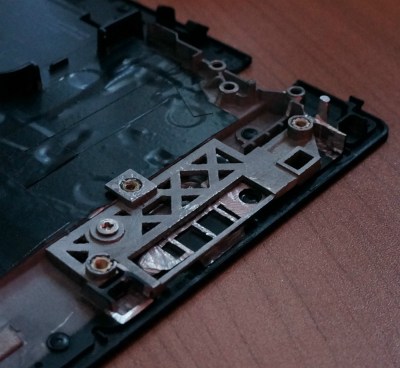

In the end, it took a lot of trimming, gluing, hacking, and fiddling to get all the new hardware from the T480 to fit into the T25. But if you’re brave enough, the process has been detailed exquisitely by [kitsunyan]. Not only are the part numbers listed for everything you need to order, but there’s plenty of pictures to help illustrate the modifications that need to be made to all the clips, brackets, and assorted widgets that go into a modern laptop.

While we’re very impressed by this project, we can’t say it comes as a complete surprise. We’re well aware of the incredible lengths Thinkpad aficionados will go to keep their machines running into the 21st century. But don’t just take our word for it, you too can join the ranks of the Thinkpad elite.

[Thanks to Pierre for the tip.]