It certainly seems as though it should be an easy enough project; all [Miguel De Andrade] wanted was to receive a notification when somebody was pressing his doorbell, and thought it would be a good project to get his feet wet in the wonderful world of ESP8266 hacking. But as fate would have it, not everything went according to plan. In the end he got it sorted out, but it’s an interesting look at how even the “easy” projects can call the gremlins out of hiding.

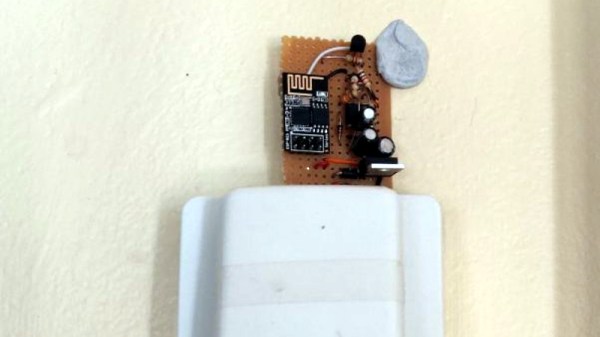

Arguably, the problems started when [Miguel] picked up an ESP-01 module from a local electronics retailer. While the convenience of buying the hardware in a brick and mortar store can’t be overstated, it did mean he was stuck with a slightly more spartan experience compared to the more common ESP “development boards”. Programming it externally with a Teensy ended up not being much of an obstacle, but it did mean he was stuck with only two GPIO pins.

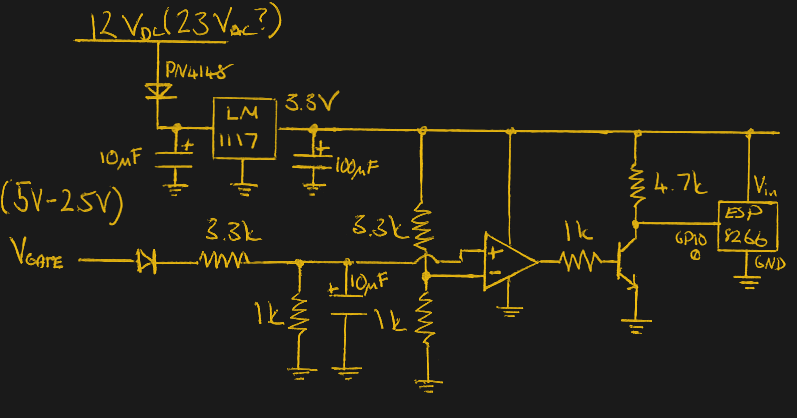

At any rate, with ESP in hand, the next step was figuring out how the existing bell and intercom system even worked. Unfortunately, after some experimentation [Miguel] found there was a bit more going on there than he’d hoped. According to his multimeter, the one line from the intercom sits at approximately 5 VDC when it’s open, and drops down to 2.5 VDC when pressed. If that wasn’t bad enough, picking up the handset to answer the intercom sent the voltage up to a microcontroller-killing 12 VDC. To complicate maters further, the supply line for the intercom was 23 VAC, so he’d need to rectify that somehow if he wanted to avoid a separate power supply for the ESP.

To turn this jumble of voltages into a nice clean 0 – 3.3 V signal for the ESP8266, he came up with a circuit based around the LM358 comparator that utilizes an LM117 regulator to power itself and the ESP at the same time. A couple of diodes are there to block the AC component from causing trouble, and an A2N2222A transistor is used as a buffer amplifier to boost the output of the comparator so it registers as a digital HIGH on the ESP. The circuit took a bit of fiddling to get sorted out, but in the end [Miguel] says it seems to get the job done.

To turn this jumble of voltages into a nice clean 0 – 3.3 V signal for the ESP8266, he came up with a circuit based around the LM358 comparator that utilizes an LM117 regulator to power itself and the ESP at the same time. A couple of diodes are there to block the AC component from causing trouble, and an A2N2222A transistor is used as a buffer amplifier to boost the output of the comparator so it registers as a digital HIGH on the ESP. The circuit took a bit of fiddling to get sorted out, but in the end [Miguel] says it seems to get the job done.

You might think the problems were solved, but this is where it gets really annoying. The system would work fine for awhile, and then inexplicably go silent. In diagnosing the problem he realized that his circuit connected to GPIO_0 was inadvertently putting the ESP8266 into programming mode, since it was holding the pin LOW unless the intercom button was pressed. He assumed he could just move the circuit to the other GPIO pin, but as that one has the board’s LED on it, that caused its own problems. For now, [Miguel] hasn’t come up with a solution to this issue, and has learned to live with the fact that the system won’t come back up cleanly should it lose power for any reason.

If you’re looking for a slightly classier look than a scrap of perfboard stuck on the wall with what appears to be chewing gum, we’ve also seen the ESP8266 used in some more ornate doorbell setups. Of course if you still haven’t gotten your head wrapped around the whole Internet-connected button thing, you can always start with something a little easier.