We have semi-fond memories of string art from our grade school art class days. We recall liking the part where we all banged nails into a board, but that bit with wrapping the thread around the nails got a bit tedious. This CNC string art machine elevates the art form far above the grammar school level without all the tedium.

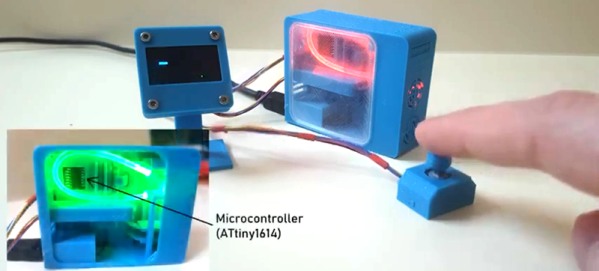

Inspired by a string art maker we recently feature, [Bart Dring] decided to tackle the problem without using an industrial robot to dispense the thread. Using design elements from his recent coaster-creating polar plotter, he built a large, rotating platform flanked by a thread handling mechanism. The platform rotates the circular “canvas” for the portrait, ringed with closely spaced nails, following G-code generated offline. A combination of in and out motion of the arm and slight rotation of the platform wraps the thread around each nail, while rotating the platform pays the thread out to the next nail. Angled nails cause the thread to find its own level naturally, so no Z-axis is needed. The video below shows a brief glimpse of an additional tool that seems to coax the threads down, too. Mercifully, [Bart] included a second fixture to drill the hundreds of angled holes needed; the nails appear to be inserted manually, but we can think of a few fixes for that.

We really like this machine, both in terms of [Bart]’s usual high build-quality standards and for the unique art it creates. He mentions several upgrades before he releases the build files, but we think it’s pretty amazing as is.

Continue reading “Polar Platform Spins Out Intricate String Art Portraits”