The future is autonomous robots. Whether that means electric cars with rebranded adaptive cruise control, or delivery robots that are actually just remote control cars, the robots of the future will need to decide how to move, where to move, and be capable of tracking their own movement. This is the problem of odometry, or how far a robot has traveled. There are many ways to solve this problem, but GPS isn’t really accurate enough and putting encoders on wheels doesn’t account for slipping. What’s really needed for robotic odometry is multiple sensors, and for that we have [Pablo] and [Alfonso]’s entry to the Hackaday Prize, the IMcorder.

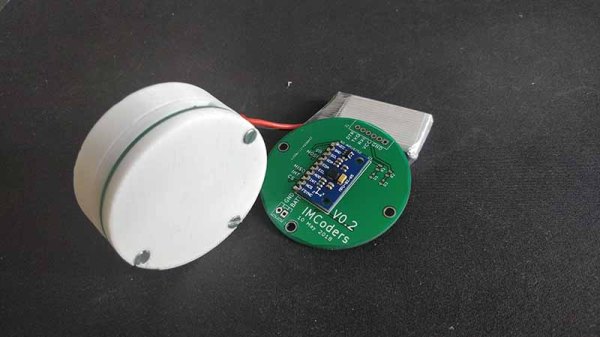

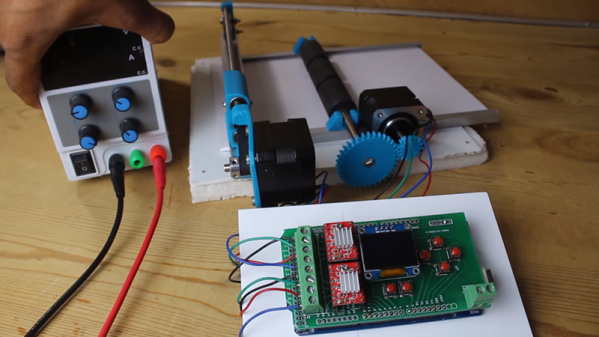

The IMcorder is a simple device loaded up with an MPU9250 IMU module that has an integrated accelerometer, gyro, and compass. This is attached to an Arduino Pro Mini and a Bluetooth module that allows the IMcorder to communicate with a robot’s main computer to provide information about a robot’s orientation and acceleration. All of this is put together on a fantastically tiny PCB with a lithium battery, allowing this project to be integrated into any robotics project without much, if any, modification.

One interesting aspect of the IMcorders is that they can be used for robot kidnapping issues. This, apparently, is an issue when it comes to robots and other electronic detritus littering the sidewalks. Those electric scooters abandoned on the sidewalk in several cities contain some amazing components that are ripe for some great hardware hacking. Eventually, we’re going to see some news stories about people stealing scooters and delivery robots for their own personal use. Yes, it’s a cyberpunk’s dream, but the IMcorder can be used for a tiny bit of theft prevention. Pity that.