It’s a problem common to every hackerspace, university machine shop, or even the home shops of parents with serious control issues: how do you make sure that only trained personnel are running the machines? There are all kinds of ways to tackle the problem, but why not throw a little tech at it with something like this magnetic card-reader machine lockout?

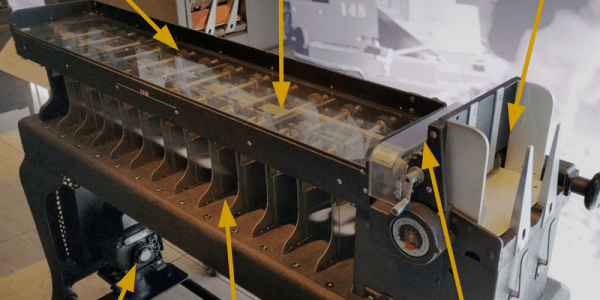

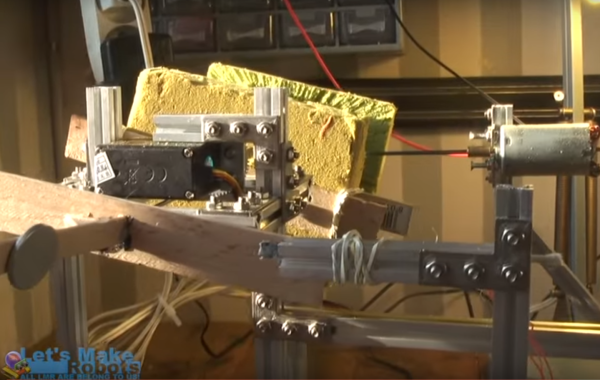

[OnyxEpoch] does not reveal which of the above categories he falls into, if any, but we’ll go out on a limb and guess that it’s a hackerspace because it would work really well in such an environment. Built into a sturdy steel enclosure, the guts are pretty simple — an Arduino Uno with shields for USB, an SD card, and a data logger, along with an LCD display and various buttons and switches. The heart of the thing is a USB magnetic card reader, mounted to the front of the enclosure.

To unlock the machine, a user swipes his or her card, and if an administrator has previously added them to the list, a relay powers the tool up. There’s a key switch for local override, of course, and an administrative mode for programming at the point of use. Tool use is logged by date, time, and user, which should make it easy to identify mess-makers and other scofflaws.

We find it impressively complete, but imagine having a session timeout in the middle of a machine operation would be annoying at the least, and potentially dangerous at worst. Maybe the solution is a very visible alert as the timeout approaches — a cherry top would do the trick!

There’s more reading if you’re one seeking good ideas for hackerspace. We’ve covered the basics of hackerspace safety before, as well as insurance for hackerspaces.

Continue reading “Card Reader Lockout Keeps Unauthorized Tool Users At Bay”