The Internet is a strange place. The promise of cyberspace in the 1990s was nothing short of humanity’s next greatest achievement. For the first time in history, anyone could talk to anyone else in a vast, electronic communion of enlightened thought, and reasoned discourse. The Internet was intended to be the modern Library of Alexandria. It was beautiful, and it was the future. The Internet was the greatest invention of all time.

Somewhere, someone realized people have the capacity to be idiots. Turns out nobody wants to learn anything when you can gawk at the latest floundering of your most hated celebrity. Nobody wants to have a conversation, because your confirmation bias is inherently flawed and mine is much better. Politics, religion, evolution, weed, guns, abortions, Bernie Sanders and Kim Kardashian. Video games.

A funny thing happened since then. People started to complain they were being pandered to. They started to blame media bias and clickbait. People started to discover that headlines were designed to get clicks. You’ve read Moneyball, and know how the use of statistics changed baseball, right? Buzzfeed has done the same thing with journalism, and it’s working for their one goal of getting you to click that link.

Now, finally, the Buzzfeed editors may be out of a job. [Lars Eidnes] programmed a computer to generate clickbait. It’s all done using recurrent neural networks gathering millions of headlines from the likes of Buzzfeed and the Gawker network. These headlines are processed, and once every twenty minutes a new story is posted on Click-O-Tron, the only news website you won’t believe. There’s even voting, like reddit, so you know the results are populist dross.

I propose an experiment. Check out the comments below. If the majority of the comments are not about how Markov chains would be better suited in this case, clickbait works. Prove me wrong.

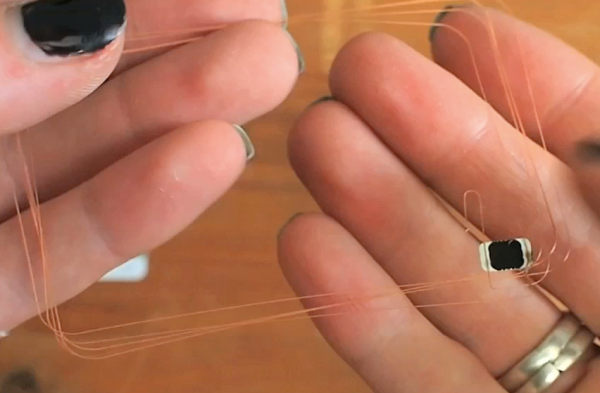

You’ll want to check out the video below to see the electronic base very nonchalantly striking the bottom of the handbell. It makes a nice ring and brings a smile to your face at how clever [Iam5volt] was with the fabrication. There aren’t any hints available on that video, but we searched around and found

You’ll want to check out the video below to see the electronic base very nonchalantly striking the bottom of the handbell. It makes a nice ring and brings a smile to your face at how clever [Iam5volt] was with the fabrication. There aren’t any hints available on that video, but we searched around and found