Oscilloscopes are especially magical because they translate the abstract world of electronics into something you can visualize. These days, a scope is likely to use an LCD or another kind of flat electronic display, but the gold standard for many years was the ubiquitous CRT (cathode ray tube). Historically, though, CRTs were not very common in the early days of electronics and radio. What we think of as a CRT didn’t really show up until 1931, although if you could draw a high vacuum and provide 30 kV, there were tubes as early as 1919. But there was a lot of electronics work done well before that, so how did early scientists visualize electric current? You might think the answer is “they didn’t,” but that’s not true. We are spoiled today with high-resolution electronic displays, but our grandfathers were clever and used what they had to visualize electronics.

Keep in mind, you couldn’t even get an electronic amplifier until the early 1900s (something we’ve talked about before). The earliest way to get a visual idea of what was happening in a circuit was purely a manual process. You would make measurements and draw your readings on a piece of graph paper.

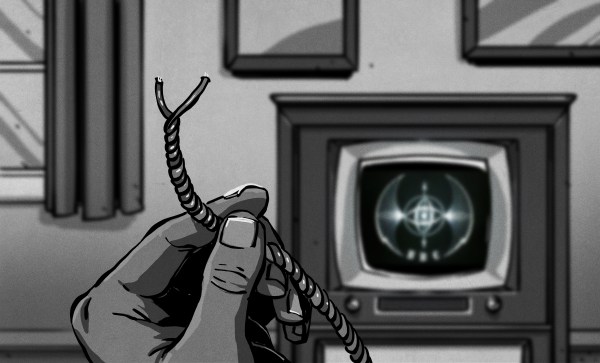

Housed on a standard-sized British electrical fascia was a 12-position rotary switch, marked with letters A through L. An unexpected thing to see in the 21st century and one probably unfamiliar to most people under about 40, I’d found something I’d not seen since my university days in the early 1990s: a Rediffusion selector switch.

Housed on a standard-sized British electrical fascia was a 12-position rotary switch, marked with letters A through L. An unexpected thing to see in the 21st century and one probably unfamiliar to most people under about 40, I’d found something I’d not seen since my university days in the early 1990s: a Rediffusion selector switch.