Photographic enthusiasts will invariably amass an extensive collection of lenses, and in their communities there are near-mythical and sought-after lenses that change hands for incredible prices. It’s probably the oldest photographic adage though, that the best camera in the world is the one in your hand when the scene presents itself, and probably one of the simplest cameras in the world remains the disposable film camera. Their tiny plastic lenses are not in the same league as the pricey ones, but can they be used by a more serious photographer? [Volzo] set out to find out.

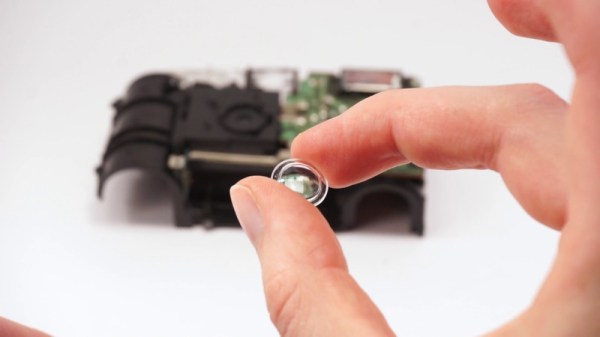

Disposable cameras aren’t the most environmentally friendly items, and he rightly points out that a cheap compact camera can deliver the same in a more sustainable package. There’s also the point to make that the flash capacitor if it has one can deliver a nasty shock, but once past that it’s easy to remove the lens itself.

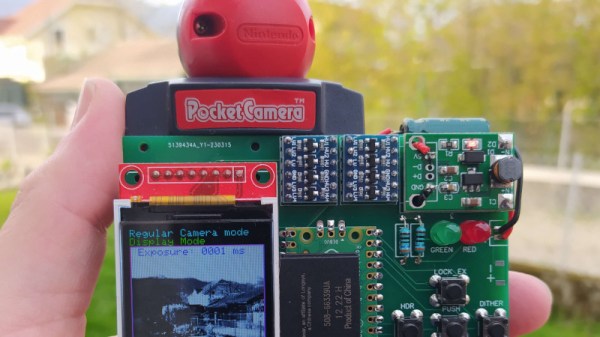

A single element lens brings with it some significant distortion, and it’s a surprise to find that the focal plane of a disposable camera is curved to take account of that. His first 3D printed mount and adapter for a Sony mirrorless compact camera uses a small aperture to reduce the distortion effects from the edge of the lens but he’s not out of tricks yet. Using a pair of the lenses back-to-back he halves the focal length but further corrects the distortion and delivers a consequent wider angle. Take a look, in the video below.

The result is a usable lens for the toy-camera look on your digital camera, and since the files can all be found at the link above it’s something you can try too. If a disposable camera comes our way, we certainly will.

This isn’t the first disposable camera lens project we’ve brought you.

Continue reading “Probably The Cheapest Lens You Will Ever Use” →

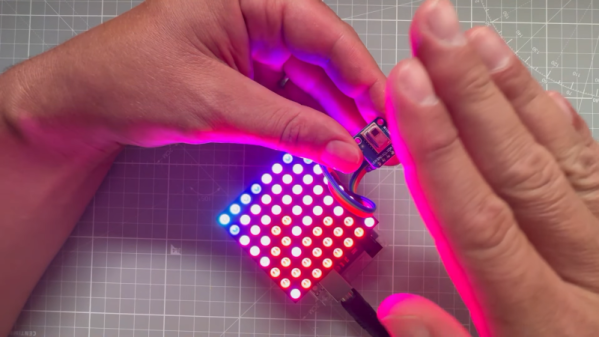

In building a new lens for the Open Sauce ’23 event, [scealux] wanted to get variable aperture working, while also improving focus speed. The lens was also intended for use with a Sony A7R3. Unlike his previous effort, this lens would only work on the full-frame Sony FE mount cameras.

In building a new lens for the Open Sauce ’23 event, [scealux] wanted to get variable aperture working, while also improving focus speed. The lens was also intended for use with a Sony A7R3. Unlike his previous effort, this lens would only work on the full-frame Sony FE mount cameras.