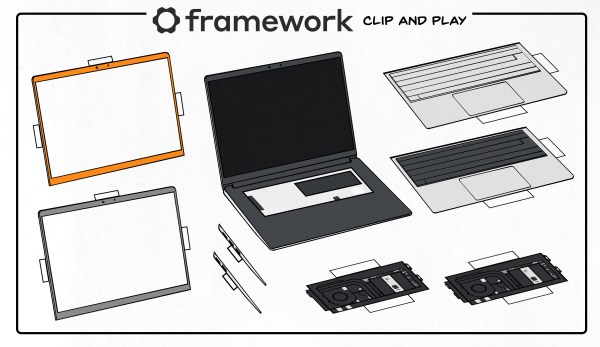

We’ve been keeping an eye on the Framework laptop over the past two years – back in 2021, they announced a vision for a repairable and hacker-friendly laptop based on the x86 architecture. They’re not claiming to be either open-source or libre hardware, but despite that, they have very much delivered on repairability and fostered a hacker community around the laptop, while sticking to pretty ambitious standards for building upgradable hardware that lasts.

I’ve long had a passion for laptop hardware, and when Hackaday covered Framework announcing the motherboards-for-makers program, I submitted my application, then dove into the ecosystem and started poking at the hardware internals every now and then. A year has passed since then, and I’ve been using a Framework as a daily driver, reading the forums on the regular, hanging out in the Discord server, and even developed a few Framework accessories along the way. I’d like to talk about what I’ve seen unfold in this ecosystem, both from Framework and the hackers that joined their effort, because I feel like we have something to learn from it.

If you have a hacker mindset, you might be wondering – just how much is there to hack on? And, if you have a business mindset, you might be wondering – how much can a consumer-oriented tech company achieve by creating a hacker-friendly environment? Today, I’d like to give you some insights and show cool things I’ve seen happen as an involved observer, as well as highlight the path that Framework is embarking upon with its new Framework 16.

Continue reading “How Framework Laptop Broke The Hacker Ceiling”