The 2022 Hackaday Prize is focused on lightening our load on the planet, and one obvious way to do so is to get and store renewable power locally — the theme of our first challenge round: Planet-Friendly Power. Our judges have studied all the entries and their votes are in. All of these ten projects will receive $500 right now and are eligible for the Grand Prize of $50,000, to be announced in November.

Most of the alternative energy sources you’d expect to see were represented: solar, wind, and water. But everyone brought their own twists to the topic. For instance, the Low Cost Solar Panel Solution demonstrates that there’s a lot more to a DIY solar project than just the panel. You need to support it, protect it, turn it to face the sun, and convert and store the power harvested. And [JP Gleyzes] even goes so far as to use recycled water bottles to make the 3D-printed parts. Sun Chaser 2 puts the panel on wheels, driving it out of the shade to collect maximum energy in a real-world backyard situation. Cute!

Most of the alternative energy sources you’d expect to see were represented: solar, wind, and water. But everyone brought their own twists to the topic. For instance, the Low Cost Solar Panel Solution demonstrates that there’s a lot more to a DIY solar project than just the panel. You need to support it, protect it, turn it to face the sun, and convert and store the power harvested. And [JP Gleyzes] even goes so far as to use recycled water bottles to make the 3D-printed parts. Sun Chaser 2 puts the panel on wheels, driving it out of the shade to collect maximum energy in a real-world backyard situation. Cute!

Finally, we had two great kite projects to harvest wind with minimal setups on the go: Kite Propulsion and Energy Independence While Travelling. Both are still in the experimental stages, but both have great documentation of where the research projects stand.

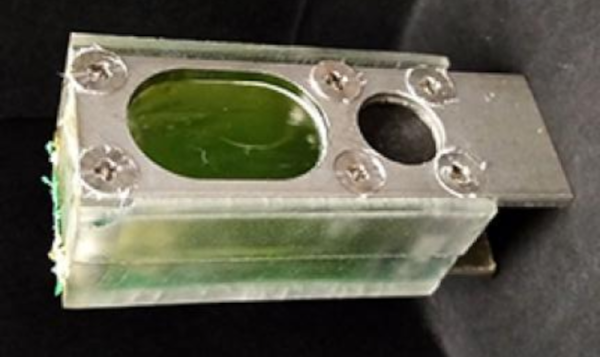

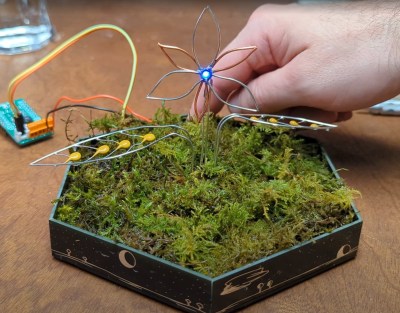

Finally, Moss Microbial Fuel Cell is really out there on the edge of current research. Combining the reasonably well established microbial fuel cell with the photosynthetic power of moss, [Guru-san] is able to light an LED for a few seconds at a time. It’s not much, but it’s also a desktop-scale project. And who can say no to leaf-shaped capacitor circuit sculptures to store the energy?

Finally, Moss Microbial Fuel Cell is really out there on the edge of current research. Combining the reasonably well established microbial fuel cell with the photosynthetic power of moss, [Guru-san] is able to light an LED for a few seconds at a time. It’s not much, but it’s also a desktop-scale project. And who can say no to leaf-shaped capacitor circuit sculptures to store the energy?

Hacker Power!

Those are just a few of the ten finalists, listed here in no particular order. Congratulations to all of you! We’re excited to follow your projects along their journey, and wish you all the best.