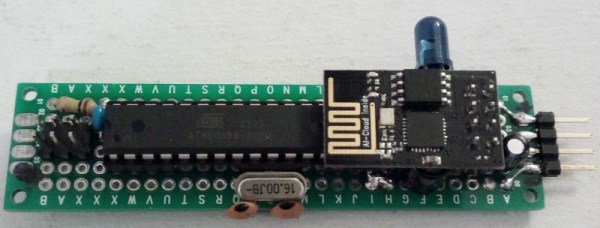

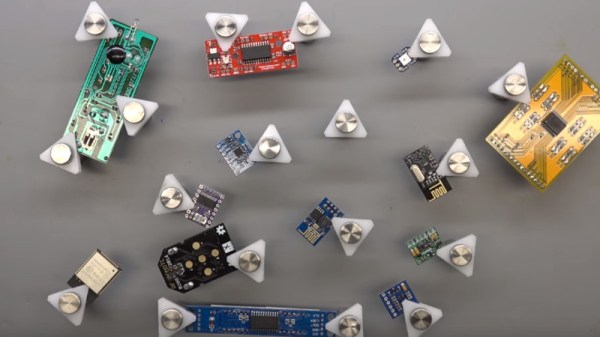

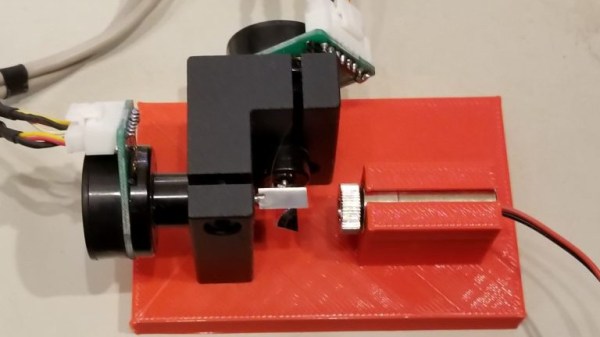

Model rocketry hobbyists are familiar with the need to roll their own solutions when putting high-tech features into rockets, and a desire to include a microcontroller in a rocket while still keeping things flexible and modular is what led [concretedog] to design a system using 22 mm diameter stackable PCBs designed to easily fit inside rocket bodies. The system uses a couple of 2 mm threaded rods for robust mounting and provides an ATTiny85 microcontroller, power control, and an optional small prototyping area. Making self-contained modular sleds that fit easily into rocket bodies (or any tube with a roughly one-inch inner diameter) is much easier as a result.

The original goal was to ease the prototyping of microcontroller-driven functions like delayed ignition or altimeter triggers in small Estes rockets, but [concretedog] felt there were probably other uses for the boards as well and made the design files available on GitHub. (Thanks!)

We have seen stackable PCBs for rocketry before with the amazingly polished M3 Avionics project, but [concretedog]’s design is much more accessible to some hobbyist-level tinkering; especially since the ATTiny85 can be programmed using the Arduino IDE and the boards themselves are just an order from OSH Park away.

[via Dangerous Prototypes Blog]