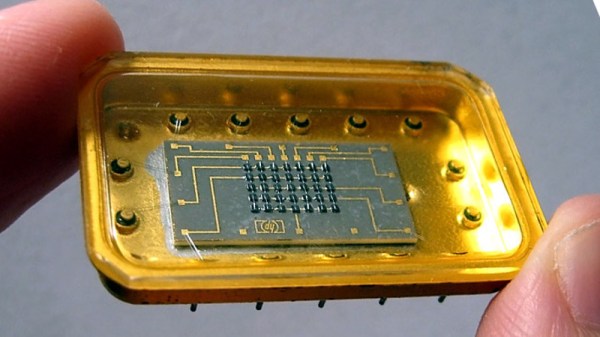

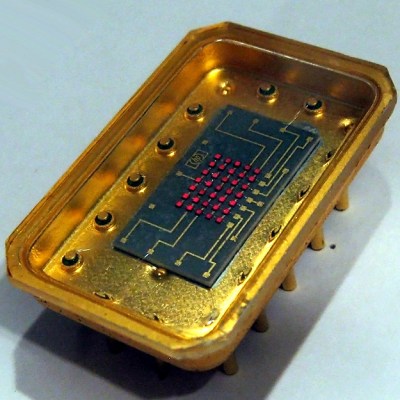

Early LED displays came in all sorts of configurations. Because the LED was fairly new technology, all kinds of ideas were getting tried, and with all that work there was plenty of opportunity for hardware that didn’t make the cut to fall into obscurity. That’s exactly what happened to the Hewlett-Packard 5082-7002, a 5×7 LED matrix display with something many of its brethren didn’t: an oversized gold tub to sit in.

It doesn’t seem that these displays were ever used in any actual products, and its origins are a mystery, but the device itself was nevertheless assigned an HP part number. Beyond that, not much is known about them, but [Industrial Alchemy] reminds us that many early LED devices were poorly documented and never produced in any real quantities. They became forgotten hardware, waiting to be rediscovered.

It doesn’t seem that these displays were ever used in any actual products, and its origins are a mystery, but the device itself was nevertheless assigned an HP part number. Beyond that, not much is known about them, but [Industrial Alchemy] reminds us that many early LED devices were poorly documented and never produced in any real quantities. They became forgotten hardware, waiting to be rediscovered.

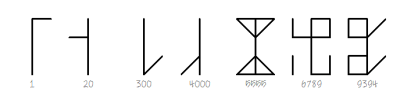

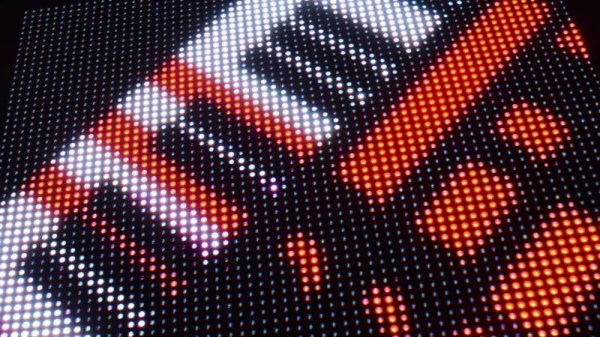

The 5082-7002 has a oversized gold tub that makes the 5×7 LED matrix mounted inside look puny by comparison, and reading any display made from these units would be difficult because the large size of the device would mean a lot of empty space between each character or digit. But it’s definitely got a striking look to it, no doubt about that.

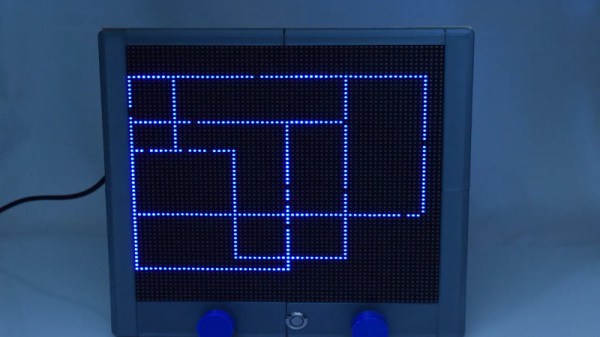

What’s neat is that the 5802-7002 actually showed up in a video we featured with a look back at cool old LED technology. If you would like to (briefly) see the HP 5802-7002 a bit closer under a microscope, here is a link to the video, cued to 2:19.