Most smart home products are designed to be controlled from a mobile device, which makes sense since that’s what the average consumer spends most of their day poking around on these days. But you aren’t the average consumer, are you? If you’re looking for a somewhat more tactile experience, then why not put your smart home dashboard on a vintage serial terminal as [Daniel Karpantschof] did?

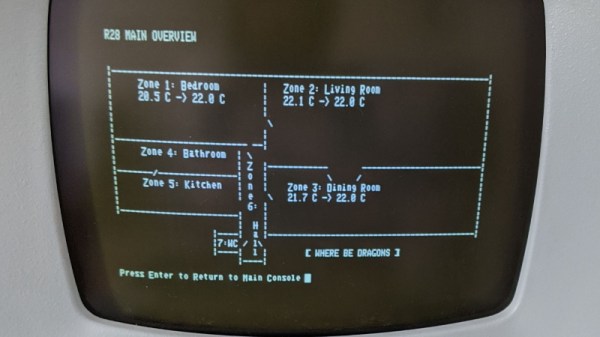

So how do you get the latest and greatest in home automation talking to a serial terminal built before the Internet as we know it? With Python, of course. [Daniel] has some code running on a Linux server that’s actually taking to his various smart home gadgets, which then spits out a simple ASCII user interface that his circa 1976 ADM-3A terminal can handle; complete with a floor plan view of the house that shows the temperature in different rooms.

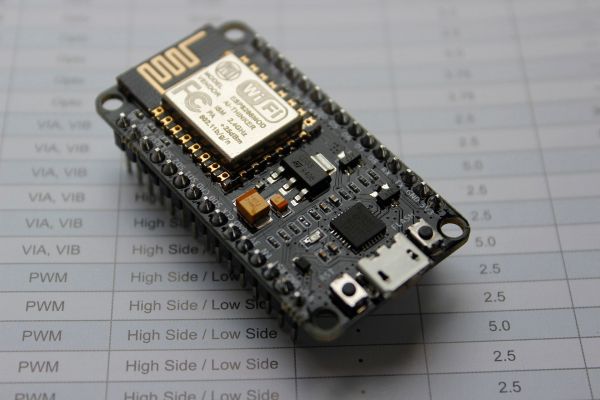

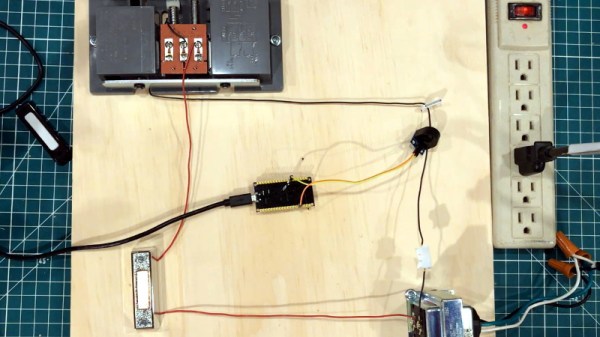

Naturally, that’s only half the battle. You still need to get that interface onto the terminal. For that, [Daniel] is using the “Simulant Retro WiFi Modem” that we’ve covered in the past. An ESP8266 connects to the network and shuffles data over to the target device over serial. It’s all transparent to the terminal itself, so this project could be reproduced with whatever vintage machine holds a special place in your heart.