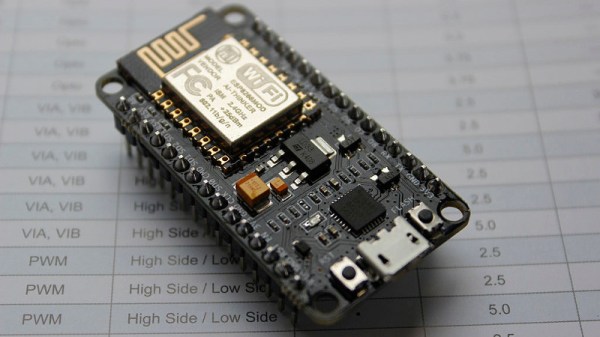

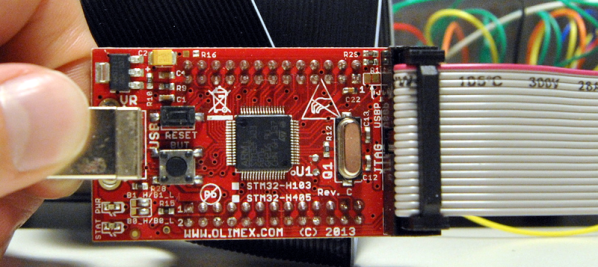

If your interest has been piqued by the inexpensive wireless-enabled goodness of the ESP8266 microcontroller, but you have been intimidated by the slightly Wild-West nature of the ecosystem that surrounds it, help is at hand. [Alexander] is creating a series of ESP8266 tutorials designed to demystify the component and lead even the most timid would-be developer to a successful first piece of code.

If you cast your mind back to 2014 when the ESP8266 first emerged, it caused great excitement but had almost no information surrounding it. You could buy it on a selection of modules, but there were no English instructions and no tools to speak of. A community of software and hardware hackers set to work, resulting in a variety of routes into development including the required add-ons to use the ever-popular Arduino framework. Four years later we have a mature and reliable platform, with a selection of higher-quality and well supported boards to choose from alongside that original selection.

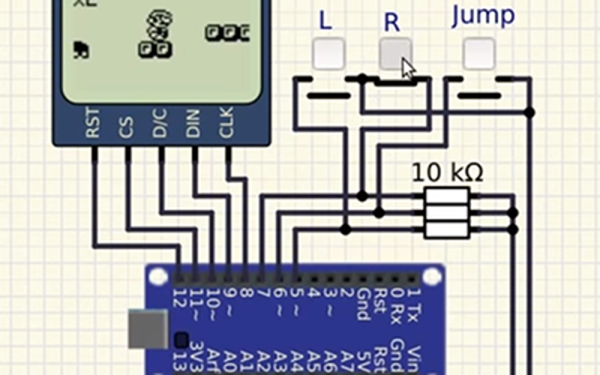

The tutorials cover the Arduino and the ESP, as well as Lua and the official SDK. They are written for a complete newcomer, but the style is accessible enough that anyone requiring a quick intro to each platform should be able to gain something.

Our community never ceases to amaze us with the quality of the work that emerges from it. We’ve seen plenty of very high quality projects over the years, and it’s especially pleasing to see someone such as [Alexander] giving something back in this way. We look forward to future installments in this series, and you should keep an eye out for them.