There’s a sinking feeling when a firmware upgrade to a piece of equipment goes wrong. We’ve all likely had this happen and bricked a device or two. If we are lucky we can simply reapply the upgrade or revert to a previous version, and if we’re unlucky we have to dive into a serial debug port to save the device from the junk pile. But what happens when both those routes fail? If you are [Arko], you reverse-engineer the device and write your own bootloader for it.

The offending bricked object was a Monoprice MP Mini Delta 3D printer to which he was foolhardy enough to apply new firmware after seeing a friend’s machine taking it without issue. Finding the relevant debug interface on its main PCB he applied the firmware upgrade again, only to realise that in doing so he had overwritten its bootloader. The machine seemed doomed, but he wasn’t ready to give up.

What follows in his write-up is a detailed examination of the boot mechanism and memory map of an ARM Cortex M0 processor as found in the Monoprice’s STM32F070CB. We learn about vector tables for mapping important addresses of interrupts and execution points, and the mechanics of a bootloader in setting up the application it launches. This section is well worth a read on its own, even for those with no interest in bricked 3D printers.

In the end he had a working bootloader to which he appended the application firmware, but sadly when he powered up the printer there was still no joy. The problem was traced to the serial connection between the ARM doing the printer’s business and the ESP8266 running its display. After a brainstorm suggestion with a friend, a piece of code was found which would set the relevant registers to allow it to run at the correct speed.

So after a lot of work that resulted in this fascinating write-up, there was a working 3D printer. He suggests that mere mortals try asking Monoprice for a replacement model if it happens to their printers, but we’re extremely glad he persevered. Without it we would never have had this fascinating write-up, and would be the poorer without the learning experience.

This isn’t the first time we’ve brought you 3D printer bootloader trickery.

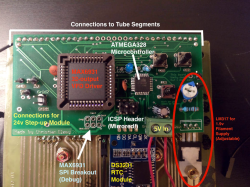

After getting the VFDs lighting up and figuring out the circuitry on the back, [InThePartsBin] decided that a clock was the best thing to build out of it. It was decided that a specialized VFD driver chip was the easiest way to make the thing work, so a MAX6934 was ordered. To give the clock some brains, an ATmega328 was recruited and to keep time, [InThePartsBin] had some DS3231 real-time clock modules left over from a previous project, so they were recruited as well. A daughterboard was designed to sit on the back of the vintage board and hold the ‘328 and the VFD driver chip.

After getting the VFDs lighting up and figuring out the circuitry on the back, [InThePartsBin] decided that a clock was the best thing to build out of it. It was decided that a specialized VFD driver chip was the easiest way to make the thing work, so a MAX6934 was ordered. To give the clock some brains, an ATmega328 was recruited and to keep time, [InThePartsBin] had some DS3231 real-time clock modules left over from a previous project, so they were recruited as well. A daughterboard was designed to sit on the back of the vintage board and hold the ‘328 and the VFD driver chip.