Have you ever been at the bookstore and stumbled across a great book you’ve been looking for, but had a nagging feeling that you already had it sitting at home? Yeah, us too. If only we’d had something like [Kutluhan Aktar]’s ISBN verifier the last time that happened to say for sure whether we already had it.

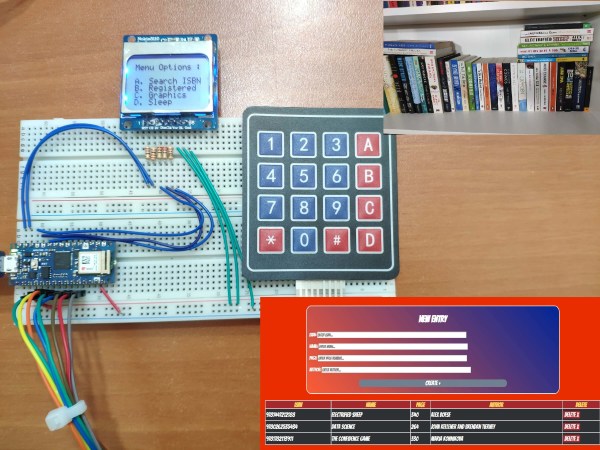

To use this handy machine, [Kutluhan] enters the International Standard Book Number (ISBN) of the book in question on the 4 x 4 membrane keypad. The Arduino Nano 33 IoT takes that ISBN and checks it against a PHP web database of book entries [Kutluhan] created with the ISBN, title, author, and number of pages. Then it lets [Kutluhan] know whether they already have it by updating the display from a Nokia 5110.

If you want to whip one of these up before your next trip to the bookstore, this project is completely open source down the web database. You might want to figure out some sort of enclosure unless you don’t mind the shy, inquisitive stares of your fellow bookworms.

Stalled out on reading because you don’t know what to read next? Check out our Books You Should Read column and get back to entertaining yourself in the theater of the mind.

Via r/duino