We usually think of the RTL-SDR as a low-cost alternative to a “real” radio, but this incredible project spearheaded by [Rodrigo Freire] shows that the two classes of devices don’t have to be mutually exclusive. After nearly 6 months of work, he’s developed and documented a method to integrate a RTL-SDR Blog V3 receiver directly into the Yaesu FT-991 transceiver.

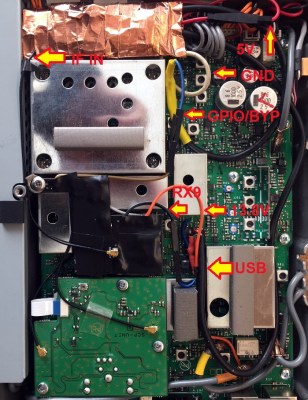

The professional results of the hack are made possible by the fact that the FT-991 already had USB capability to begin with. More specifically, it had an internal USB hub that allowed multiple internal devices to appear to the computer as a sort of composite device.

The professional results of the hack are made possible by the fact that the FT-991 already had USB capability to begin with. More specifically, it had an internal USB hub that allowed multiple internal devices to appear to the computer as a sort of composite device.

Unfortunately, the internal USB hub only supported two devices, so the first order of business for [Rodrigo] was swapping out the original USB2512BI hub IC with a USB2514BI that offered four ports. With the swap complete, he was able to hang the RTL-SDR device right on the new chip’s pins.

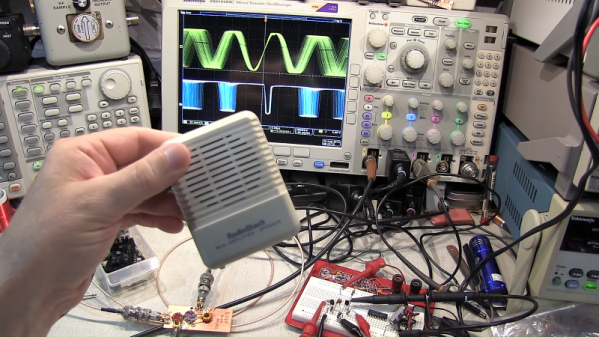

Of course, that was only half of the battle. He had a nicely integrated RTL-SDR from an external standpoint, but to actually be useful, the SDR would need to tap into the radio’s signal. To do this, [Rodrigo] designed a custom PCB that pulls the IF signal from the radio, feed it into an amplifier, and ultimately pass it to the SDR. The board uses onboard switches, controlled by the GPIO ports on the RTL-SDR Blog V3, for enabling the tap and preamplifier.

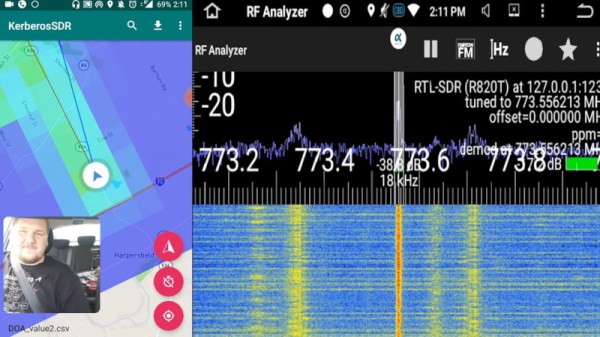

In the video after the break, you can see [Rodrigo] demonstrate his modified FT-991. This actually isn’t the first time somebody has tapped into their Yaesu with a software defined radio, though this is surely the cleanest install we’ve ever seen.