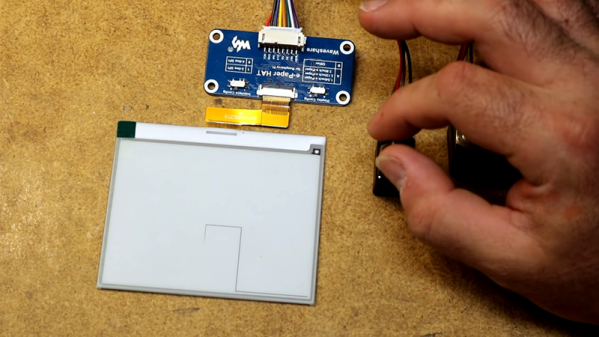

Electronic things are often most successful when they duplicate some non-electronic thing. Most screens, then, are poor replacements for paper. Except, of course, for E-paper. These displays have high contrast even in sunlight and they hold their image even with no power. When [smbakeryt] was looking at his daughter’s Etch-a-Sketch, he decided duplicating its operation would be a great way to learn about these paper-like displays.

You can see a video of his results and his findings below. He bought several displays and shows them all, including some three-color units which add a single spot color. The one thing you’ll notice is the displays are slow which is probably why they haven’t taken over the world.

The displays connect to a Raspberry Pi and many of the displays are meant to mount directly to a Pi. The largest display is nearly six inches and some of the smaller displays are even flexible. It appears the three color displays were much slower than the ones that use two colors. To combat the slow update speeds, some of the displays can support partial refresh.

The drawing toy uses optical encoders connected to the Raspberry Pi. The Python code is available. Even if you don’t want to duplicate the toy, the comparison of the displays is worth watching. We were really hoping he’d included an accelerometer to erase it by shaking, but you’ll have to add that feature yourself. By the way, in the video, he mentions the real Etch-a-Sketch might work with magnets. It doesn’t. It is an aluminum powder that sticks to the plastic until a stylus rubs it off.

We’ve seen these displays many times before, of course. If you are patient enough, you can even use them as Linux displays.

Continue reading “Using E-Paper Displays For An Electronic Etch A Sketch”

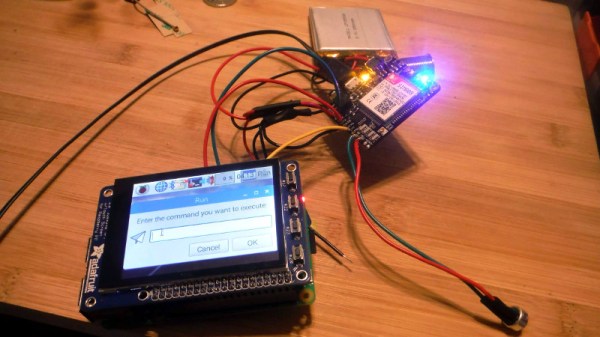

The case is 3D printed, and [Dylan] says it took a long time to nail down a design that would fit all of his hardware, keep things from shifting around, and still be reasonably slim. Obviously DIY phones like this are never going to be as slim as even the chunkiest of modern smartphones, but the rCrumbl looks fairly reasonable for a portable device. We especially like the row of physical buttons he’s included along the bottom of the screen, which should help with the device’s usability.

The case is 3D printed, and [Dylan] says it took a long time to nail down a design that would fit all of his hardware, keep things from shifting around, and still be reasonably slim. Obviously DIY phones like this are never going to be as slim as even the chunkiest of modern smartphones, but the rCrumbl looks fairly reasonable for a portable device. We especially like the row of physical buttons he’s included along the bottom of the screen, which should help with the device’s usability.