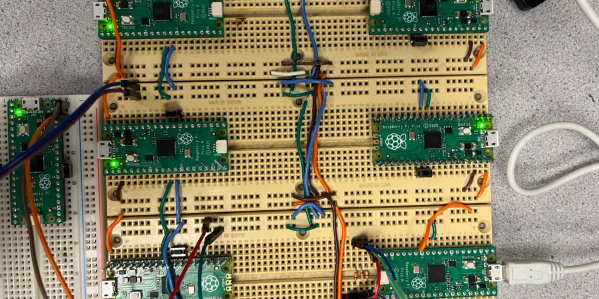

This gesture-controlled labyrinth game using two Raspberry Pi Pico units does a great job of demonstrating how it can sometimes take a lot of work to make something look simple.

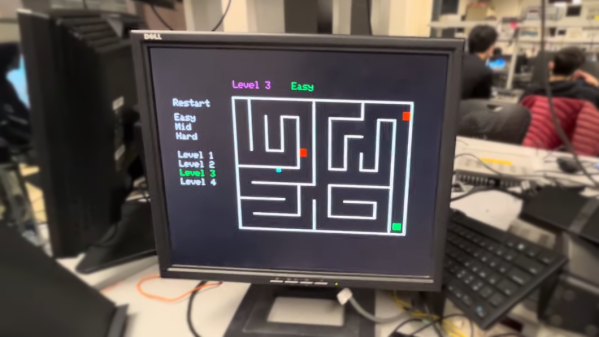

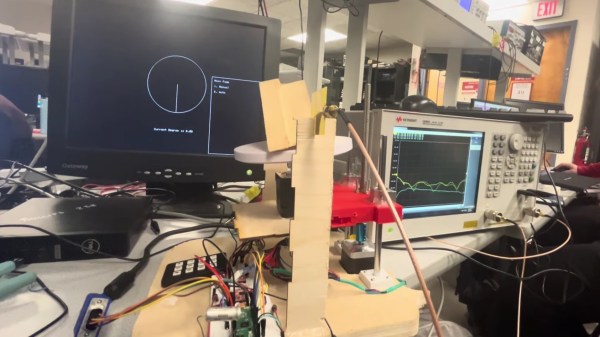

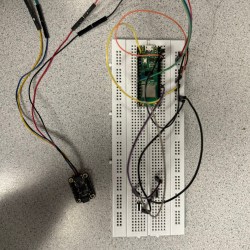

To play, one tilts an MPU6050 inertial measurement unit (IMU) attached to one Pico to guide a square through a 2D maze, with the player working through multiple levels of difficulty. A second Pico takes care of displaying the game state on a VGA monitor, and together they work wirelessly to deliver a coherent experience with the right “feel”. This includes low latency, simulating friction appropriately, and more.

To play, one tilts an MPU6050 inertial measurement unit (IMU) attached to one Pico to guide a square through a 2D maze, with the player working through multiple levels of difficulty. A second Pico takes care of displaying the game state on a VGA monitor, and together they work wirelessly to deliver a coherent experience with the right “feel”. This includes low latency, simulating friction appropriately, and more.

Taking a stream of raw sensor readings and turning them into control instructions over UDP in a way that feels intuitive while at the same time generating a VGA display signal has a lot of moving parts, software-wise. The project write-up has a considerable amount of detail on the architecture of the system, and the source code is available on GitHub for those who want a closer look.

We’ve seen gesture controls interfaced to physical marble mazes before, but two Raspberry Pi Picos doing it wirelessly with a VGA monitor for feedback is pretty neat. Watch it in action in the video, embedded just under the page break.

Continue reading “Gyro-Controlled Labyrinth Game Outputs To VGA”