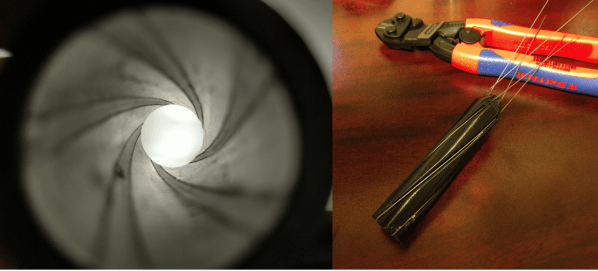

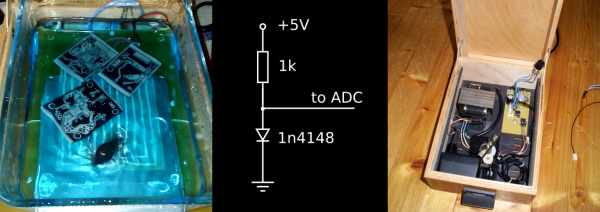

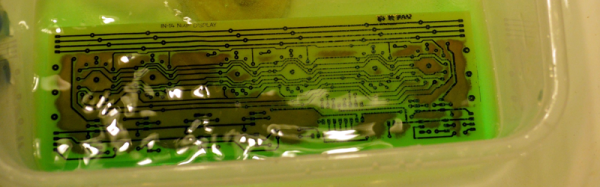

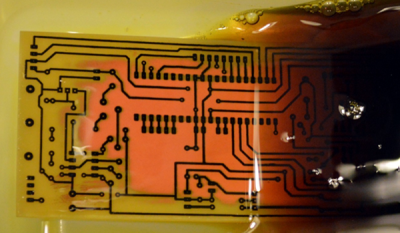

[Jeff Rodriguez] has been busy testing a feasible DIY method for rifling a barrel and has found some success using salt water, a power supply, wire, and 3D printed parts to create the grooves of rifling without the need for any moving parts or cutting tools. Salt water flows between the barrel’s inside surface and a 3D-printed piece that holds wires in a precise pattern. A current flows between the barrel and the wires (which do not actually touch the inside of the barrel) and material is eroded away as a result. 10-15 minutes later there are some promising looking grooves in the test piece thanks to his DIY process.

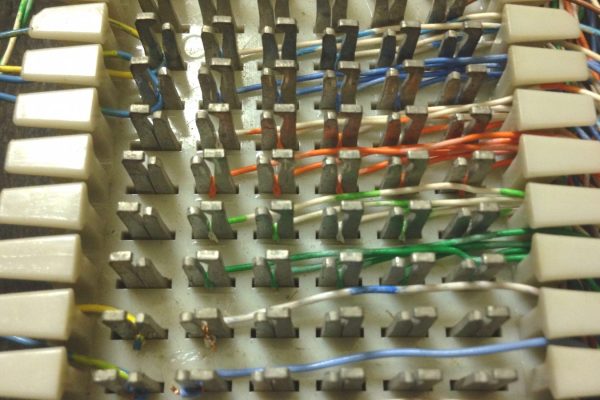

Rifled barrels have been common since at least the 19th century (although it was certainly an intensive process) and it still remains a job best left to industrial settings; anyone who needs a barrel today normally just purchases a rifled barrel blank from a manufacturer. No one makes their own unless they want to for some reason, but that’s exactly where [Jeff] is coming from. The process looks messy, but [Jeff] has had a lot of space to experiment with a variety of different methods to get different results.