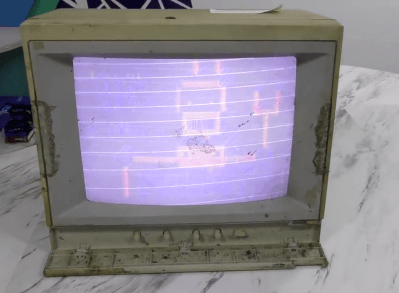

[The 8-Bit Guy] recently went to check out a stash of old Apple II Color monitors which had been sitting outside in a trash pile for 20 years, and decided to bring one home to restore. As you can see from the lead photo, they were dirty — really dirty. Surprisingly, the team of volunteers who discovered these monitors had fired them up, and every one of them works to some extent or another.

Check out the video below as he cleans up this filthy monitor and starts troubleshooting. You’ll chuckle aloud when he turns the circuit board over to desolder a mysterious diode, and when he flips the board back over, the diode has disappeared (it actually disintegrated into dust on his lab bench). For the curious, one commenter on YouTube found that it was a glass passivated and encapsulated fast recovery diode called a V19. There’s going to be a part 2, and we have every confidence that [The 8-Bit Guy] will succeed and soon add a shiny, like-new monitor to his collection.

If you’re a collector of old monitors, this demonstrates that they can survive quite a bit of abuse and exposure. We’re not sure that rummaging through your local landfill is the best idea, but if you run into an old monitor that has been exposed to the elements, don’t be so quick to dismiss it as a lost cause. Do you have any gems that you’ve restored from the trash? Let us know in the comments.