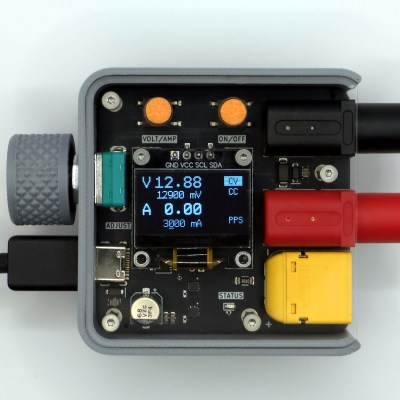

When [Tahmid Mahbub] recently reached for his ‘Lavolta’ BPS-305 bench supply, he was dismayed to find that despite it being a 30V, 5A-rated unit, the supply refused to output more than 15V. To be fair, he wasn’t sure that he had ever tried to push it beyond 15V in the years that he had owned it, but it had better live up to its specs. Ergo out came the screwdriver to open the power supply to see what had broken, and hopefully to fix it.

After some more probing around, he discovered that the unit had many more issues, including a highly unstable output voltage and output current measurement was completely wrong. Fortunately this bench power supply turns out to be very much like any number of similar 30V, 5A units, with repair videos and schematics available.

While [Tahmid] doesn’t detail his troubleshooting process, he does mention the culprits: two broken potentiometers (VR104 and VR102). VR104 is a 5 kOhm pot in the output voltage feedback circuit and VR102 (500 Ohm) sets the maximum output current. With no 500 Ohm pot at hand, a 5 kOhm one was combined with a 470 Ohm resistor to still allow for trimming. Also adjusted were the voltage and current trimpots for the front display as they were quite a bit off. Following some testing on the reassembled unit, this power supply is now back in service, for the cost of two potentiometers and a bit of time.