There’s no single formula for success, but if we’ve learned anything over the years of covering cons, contests, and hackathons, it’s that, just like in geology, pressure can create diamonds. Give yourself an impossible deadline with high stakes, and chances are good that something interesting will result. That’s what Estefannie from the YouTube channel “Estefannie Explains It All” did when Bay Area Maker Faire was rolling around last year, and she stopped by the 2018 Hackaday Superconference to talk about the interactive Daft Punk helmet that came out of it.

It’s a rapid-fire tour of Estefannie’s remarkably polished replica of the helmet worn by Guy-Manuel de Homem-Christo, one half of the French electronic music duo Daft Punk. Her quick talk, video of which is below, gives an overview of its features, but we miss the interesting backstory. For that, the second video serves as a kickoff to a whirlwind month of hacking that literally started from nothing.

You’ll Learn it Along the Way

Before deciding to make the helmet, Estefannie had zero experience in the usual tools of the trade. With only 28 days to complete everything, she had to: convert her living room into a workshop; learn how to 3D print; print 58 separate helmet parts, including a mold for thermoforming the visor; teach herself how to thermoform after building the tools to do so; assemble and finish all the parts; and finally, install the electronics that are the hallmark of Daft Punk’s headgear.

The three videos in her series are worth watching to see what she put herself through. Estefannie’s learning curve was considerable, and there were times when nothing seemed to work. The thermoforming was particularly troublesome — first too much heat, then not enough, then not enough vacuum (pretty common hurdles from other thermoforming projects we’ve seen). But the finished visor was nearly perfect, even if it took two attempts to tint.

The three videos in her series are worth watching to see what she put herself through. Estefannie’s learning curve was considerable, and there were times when nothing seemed to work. The thermoforming was particularly troublesome — first too much heat, then not enough, then not enough vacuum (pretty common hurdles from other thermoforming projects we’ve seen). But the finished visor was nearly perfect, even if it took two attempts to tint.

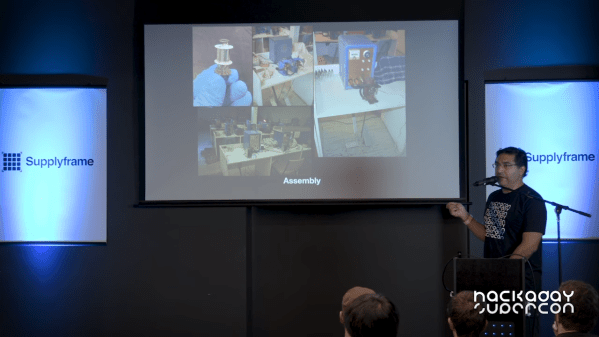

We have to say that at first, some of her wounds seemed self-inflicted, especially seeing the amount of work she put into the helmet’s finish. But she wanted it to be perfect, and the extra care in filling, sanding, priming, and painting the printed parts really paid off in the end. It was down to the wire when BAMF rolled around, with last minute assembly left to the morning of the Faire in the hotel room, but that always seems to be the way with these kinds of projects.

In the end, the helmet came out great, and we’re glad the run-up to the Superconference wasn’t nearly as stressful for Estefannie — or so we assume. And now that she has all these great new skills and tools, we’re looking forward to her next build.

Continue reading “Hackaday Superconference: Estefannie’s Daft Punk Helmet”