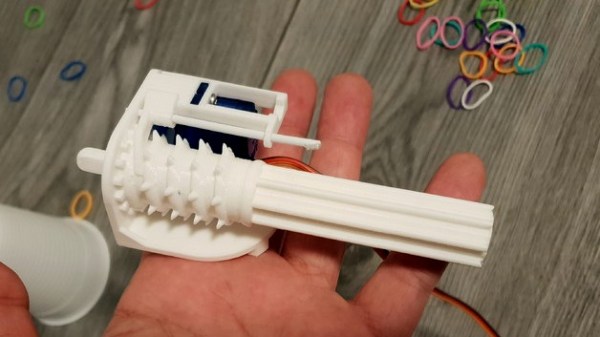

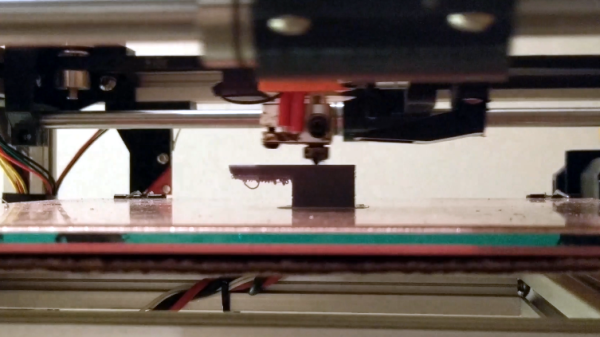

One thing 3D printers excel at is being able to easily create objects that would be daunting by other methods, something that also allows for rapid design iteration. That’s apparent in [Canino]’s palm-sized, gatling-style, motorized 32-elastic launcher.

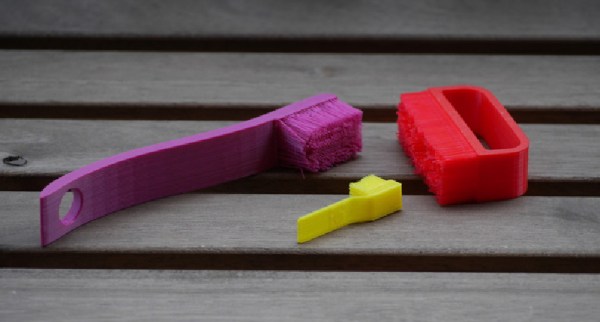

The cannon has a rotary barrel driven by a small motor, and a clever sear design uses the rotation of the barrels like a worm gear. The rotating barrel has a spiral formation of hooks which anchor the stretched elastic bands. A small ramp rides that spiral gap, lifting ends of stretched bands one at a time as the assembly turns. This movement (and therefore the firing control) is done with a small continuous rotation servo. While in theory any motor would do, using a servo has the advantage of being a standardized shape, and therefore easy to integrate into the design. A video is embedded below in which you can see it work, along with some close-ups of the action.

Continue reading “Palm-Sized Gatling Gun Has 32 Mini Elastics With Your Name On Them”

[critsrandom] shared the method

[critsrandom] shared the method