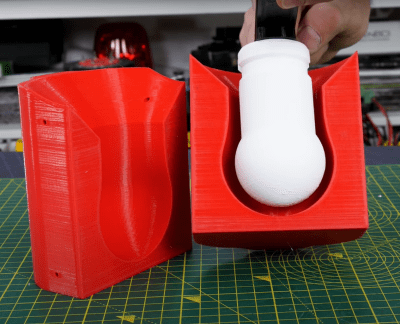

In an ideal world, your FDM 3D printer’s bed would be perfectly parallel with the print head’s plane of movement. We usually say that means the bed is “level”, but really it doesn’t matter if it is level in the traditional sense, as long as the head and the bed are the same distance apart at every point. Of course, in practice nothing is perfect.

The second best situation is when the bed is perfectly flat, but tilted relative to the print head. Even though this isn’t ideal, software can move the print head up and down in a linear fashion to compensate for the tilt. Things are significantly worse if the bed isn’t itself flat, and has irregular bumps up and down all over.

To combat that, some printer firmware supports probing the bed to determine its shape, and adjusts the print head up and down as it travels across the map. Of course, you can’t probe the bed at every possible point, so the printer will have to interpolate between the measured reference points. Marlin’s bilinear bed leveling is an example.

But if you have enough flash space and you use Marlin, you may want to try unified bed leveling (UBL). This is like bilinear leveling on steroids. Unfortunately, the documentation for this mode is not as plain as you might like. Everything is out there, but it is hard to get started and information is scattered around a few pages and videos. Let’s fix that.

Continue reading “3D Printering: One Bed Level To Rule Them All”