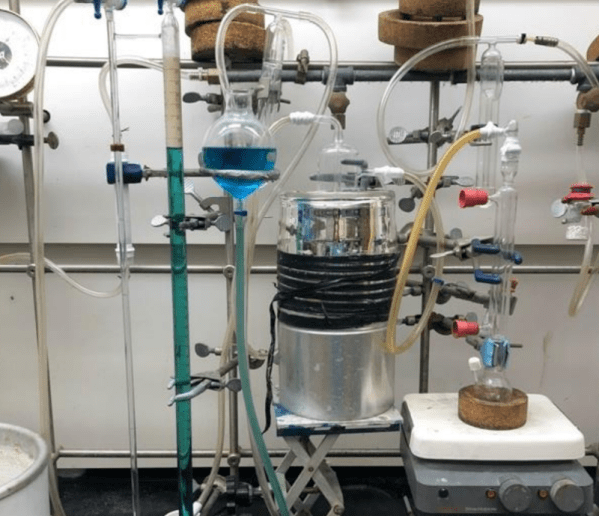

Hydrogen fuel is promising, and while there’s plenty of hydrogen in the air and water, the problem is extracting it. Researchers have developed a way to use aluminum nanoparticles to rip hydrogen out of water with no additional energy input. It does, however, require gallium to enable the reaction. The reaction isn’t unknown (see the video below), but the new research has some interesting twists.

Aluminum, of course, is cheap and plentiful. Gallium, not so much, but the process allows recovery and reuse of the gallium, so that makes it more cost-effective. There is a patent pending for the process and — of course — the real trick is making the aluminum nanoparticles. But if you have that, this is a simple way to extract hydrogen from water with no extra energy and at room temperature. Since the reaction of creating aluminum oxide and releasing hydrogen with gallium is pretty well-known, it appears the real research here is determining the optimal properties of the aluminum and the ratio of aluminum to gallium.

While gallium isn’t a common item around the typical hacker’s workshop — unless you count the stuff bound up in semiconductors — it isn’t that expensive and it is relatively easy to handle. Hydrogen, though, not so much — so if you do decide to use this method to produce hydrogen, be careful!

We’ve seen gallium robots and even an antenna. So if you do get some of the liquid metal, there are plenty of experiments to try.