They say the eyes are the windows to the soul. But with a new smartphone app, the eyes may be a diagnostic window into the body that might be used to prevent a horrible disease — pancreatic cancer. A research team at the University of Washington led by [Alex Mariakakis] recently described what they call “BiliScreen,” a smartphone app to detect pancreatic disease by imaging a patient’s eyes.

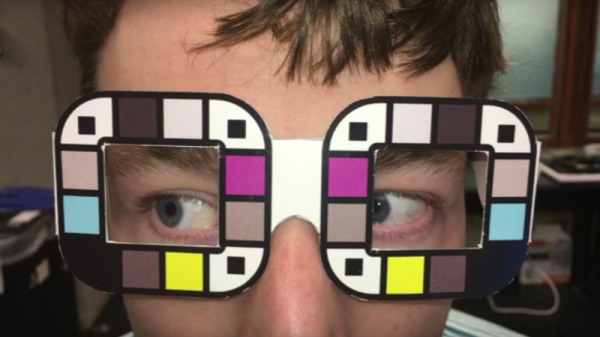

Pancreatic cancer is particularly deadly because it remains asymptomatic until it’s too late. One early symptom is jaundice, a yellow-green discoloration of the skin and the whites of the eyes as the blood pigment bilirubin accumulates in the body. By the time enough bilirubin accumulates to be visible to the naked eye, things have generally progressed to the inoperable stage. BiliScreen captures images of the eyes and uses image analysis techniques to detect jaundice long before anyone would notice. To control lighting conditions, a 3D-printed mask similar to Google’s Cardboard can be used; there’s also a pair of glasses that look like something from [Sir Elton John]’s collection that can be used to correct for ambient lighting. Results look promising so far, with BiliScreen correctly identifying elevated bilirubin levels 90% of the time, as compared to later blood tests. Their research paper has all the details (PDF link).

Tools like BiliScreen could really make a difference in the early diagnosis and prevention of diseases. For an even less intrusive way to intervene in disease processes early, we might also be able to use WiFi to passively detect Parkinson’s.