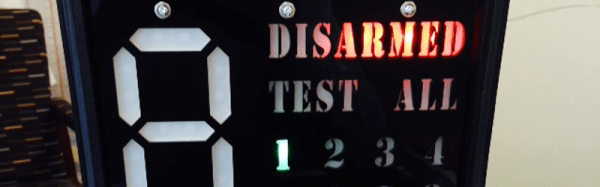

A lot of designers have the luxury of creating things that aren’t supposed to explode. That’s usually easy. The trick is designing things that are supposed to explode and then making absolutely sure they explode at the right time (and only the right time). [JonBush] recently did a beautiful build of an Arduino-based fireworks controller. Seriously, it looks like a movie prop from a summer blockbuster where [Bruce Willis] is trying to decide what wire to cut.

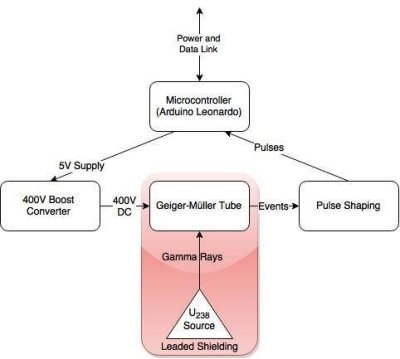

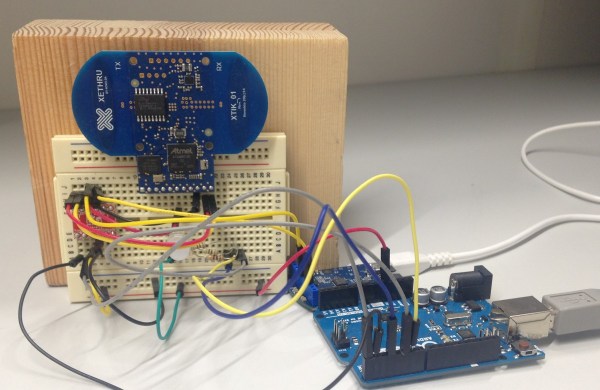

[Jon] used a mega 2560 because he wanted to do the I/O directly from the device. His code only takes about 8K of the total program storage, so with some I/O expansion (like shift registers) a smaller chip would do the job. The device can control up to 8 sets of fireworks, uses a physical arm key, and has a handheld remote. It is even smart enough to sense igniter failures.

The front panel is a work of art and includes a seven-segment display made from Neopixel LEDs. The whole thing is in a waterproof case and uses optical isolation in several key areas.