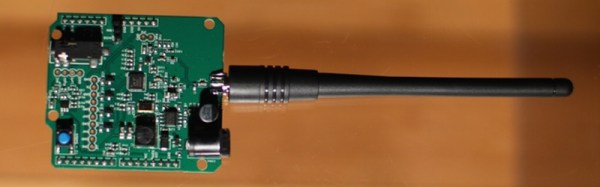

Speak with those who consider themselves hardcore engineers and you might hear “Arduinos are for noobs” or some other similar nonsense. These naysayers see the platform as a simplified, overpriced, and over-hyped tool that lets you blink a few LEDs or maybe even read a sensor or two. They might say that Arduino is great for high school projects and EE wannabes tinkering in their garage, but REAL engineering is done with ARM, x86 or PICs. Guess what? There are Arduino compatible boards built around all three of those architectures. Below you can see but three examples in the DUE, Galileo, and Fubarino SD boards.

This attitude towards Arduino exists mainly out of ignorance. So let’s break down a few myths and preconceived biases that might still be lurking amongst some EEs and then talk about Arduino’s ability to move past the makers.

Arduino is NOT the Uno

When some hear “Arduino”, they think of that little blue board that you can plug a 9v battery into and start making stuff. While this is technically true, there’s a lot more to it than that.

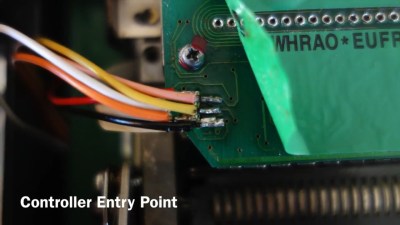

- An Arduino Uno is just an AVR development board. AVRs are similar to PICs. When someones says “I used a PIC as the main processor”, does that mean they stuck the entire PIC development board into their project? Of course not. It’s the same with Arduino (in most cases), and design is done the same way as with any other microcontroller –

- Use the development board to make, create and debug.

- When ready, move the processor to your dedicated board.

- What makes an Arduino an “Arduino” and not just an AVR is the bootloader. Thus:

- An Atmega328P is an AVR processor.

- An Atmega328P with the Arduino bootloader is an Arduino.

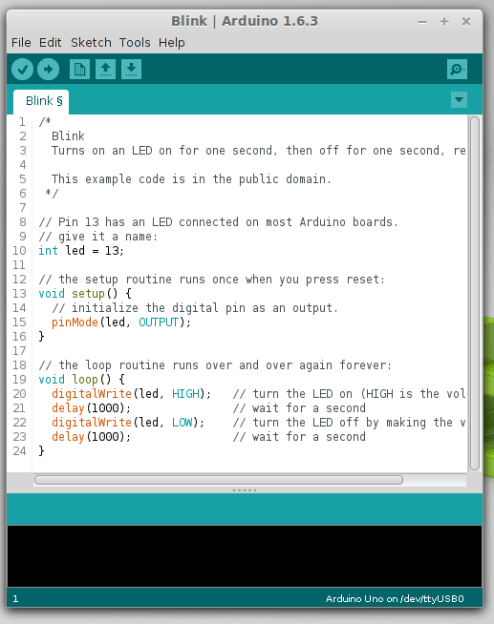

- The bootloader allows you to program the AVR with the Arduino IDE. If you remove the bootloader from the AVR, you now have an AVR development board that can be programmed with AVR Studio using your preferred language.

There Is No Special Arduino Language

Yes, I know they call them sketches, which is silly. But the fact is it’s just c++. The same c++ you’d use to program your PIC. The bootloader allows the IDE to call functions, making it easy to code and giving Arduino its reputation of being easy to work with. But don’t let the “easy” fool you. They’re real c/c++ functions that get passed to a real c/c++ compiler. In fact, any c/c++ construct will work in the Arduino IDE. With that said – if there is any negative attribute to Arduino, it is the IDE. It’s simple and there is no debugger.

The strength comes in the standardization of the platform. You can adapt the Arduino standard to a board you have made and that adaptation should allow the myriad of libraries for Arduino to work with your new piece of hardware. This is a powerful benefit of the ecosystem. At the same time, this easy of getting things up and running has resulted in a lot of the negative associations discussed previously.

So there you have it. Arduino is no different from any other microcontroller, and is fully capable of being used in consumer products along side PICs, ARMs etc. To say otherwise is foolish.

What is the Virtue of Arduino in Consumer Products?

This is Ask Hackaday so you know there’s a question in the works. What is the virtue of Arduino in consumer products? Most electronics these days have a Device Firmware Upgrade (DFU) mode that allows the end user to upgrade the code, so Arduino doesn’t have a leg up there. One might argue that using Arduino means the code is Open Source and therefore ripe for community improvements but closed-source binaries can still be distributed for the platform. Yet there are many products out there that have managed to unlock the “community multiplier” that comes from releasing the code and inviting improvements.

What do you think the benefits of building consumer goods around Arduino are, what will the future look like, and how will we get there? Leave your thoughts below!