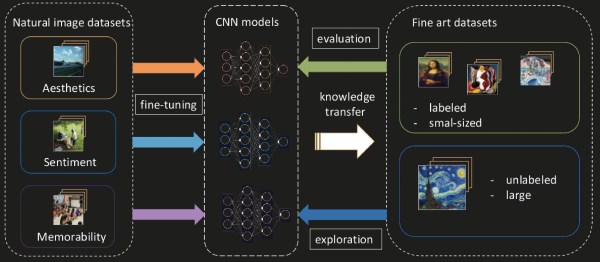

In 2019, using AI to evaluate artwork is finally more productive than foolish. We all hope that someday soon our Roomba will judge our living habits and give unsolicited advice on how we could spruce things up with a few pictures and some natural light. There is already an extensive amount of Deep Learning dedicated to photo recognition but a team in Croatia is adapting them for use on fine art. It makes sense that everything is geared toward cameras since most of us have a vast photographic portfolio but fine art takes longer to render. Even so, the collection on Wikiart.org is vast and already a hotbed for computer classification work, so they set to work there.

As they modify existing convolutional neural networks, they check themselves by comparing results with human ratings to keep what works and discard what flops. Fortunately, fine art has a lot of existing studies and commentary, whereas the majority of photographs in the public domain have nothing more than a file name and maybe some EXIF data. The difference here is that photograph-parsing AI can say, “That is a STOP sign,” while the fine art AI can say, “That is a memorable painting of a sign.” Continue reading “AI And Art Appreciation”