Sound chips from back in the day were capable of much more than a few beeps and boops, and [InazumaDenki] proves it in a video recreating recognizable real-world sounds with the AY-3-8910, a chip that was in everything from arcade games to home computers. Results are a bit mixed but it’s surprising how versatile a vintage sound chip that first came out in the late 70s is capable of, with the right configuration.

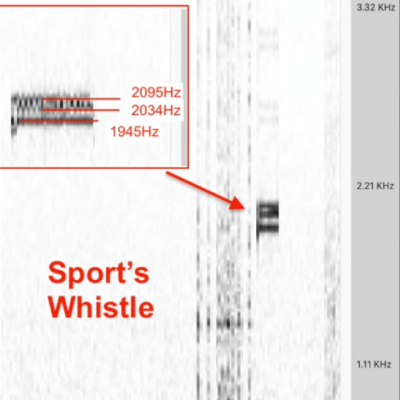

Chips like the AY-3-8910 work at a low level, and rely on being driven with the right inputs to generate something useful. It can generate up to three independent square-wave tones, but with the right approach and setup that’s enough to get outputs of varying recognizability for a pedestrian signal, bird call, jackhammer, and referee’s whistle.

To recreate a sound [InazumaDenki] begins by analyzing a recording with a spectrogram, which is a visual representation of frequency changes over time. Because real-world sounds consist of more than just one frequency (and the AY-3-8910 can only do three at once), this is how [InazumaDenki] chooses what frequencies to play, and when. The limitations make it an imperfect reproduction, but as you can hear for yourself, it can certainly be enough to do the job.

How does one go about actually programming the AY-3-8910? Happily there’s a handy Arduino AY3891x library by [Andreas Taylor] that makes it about as simple as can be to explore this part’s capabilities for yourself.

If you think retro-styled sound synthesis might fit into your next project, keep in mind that just about any modern microcontrollers has more than enough capability to do things like 80s-style speech synthesis entirely in software.

Continue reading “Hear A Vintage Sound Chip Mimic The Real World”