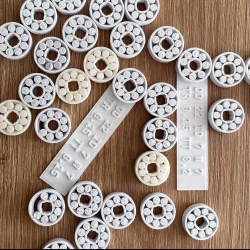

Commodity bearings are a a boon for makers who to want something to rotate smoothly, but what if you don’t have one in a pinch? [Cliff] of might have the answer for you, in the form of 3D printed bearings with filament rollers.

With the exception of the raw filament rollers, the inner and outer race, roller cage and cap are all printed. It would also be possible to design some of the components right into a rotating assembly. [Cliff] makes it clear this experiment isn’t about replacing metal bearings — far from it. Instead, it’s an inquiry into how self-sufficient one can be with a FDM 3D printer. That didn’t stop him from torture testing the design to its limits as wheel bearings on an off-road go-cart. The first version wasn’t well supported against axial loads, and ripped apart during some more enthusiastic maneuvers.

[Cliff] improved it with a updated inner race and some 3D printed washers, which held up to 30 minutes of riding with only minimal signs of wear. He also made a slightly more practical 10 mm OD version that fits over an M3 bolt, and all the design files are downloadable for free. Cutting the many pieces of filament to length quickly turned into a chore, so a simple cutting jig is also included.

Let us know in the comments below where you think these would be practical. We’ve covered some other 3D printed bearing that use printed races, as well as a slew bearing that’s completely printed. Continue reading “3D Printed Bearings With Filament Rollers”