There’s no limit to the amount of nostalgia that can be minted through various classic platforms such as the NES classic. The old titles are still extremely popular, and putting them in a modern package makes them even more accessible. On the other hand, if you still have the original hardware things can start getting fussy. With modern technology it’s possible to make some changes, though, as [PJ Allen] did by adding wireless capabilities to his Commodore 64.

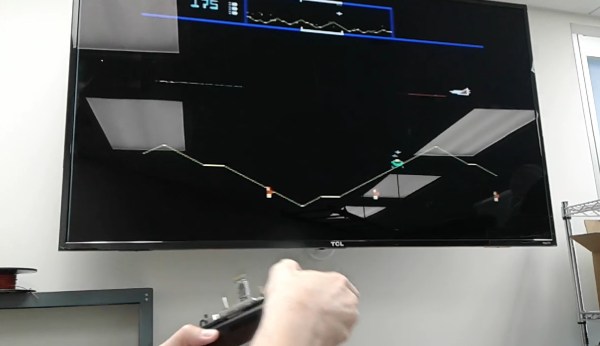

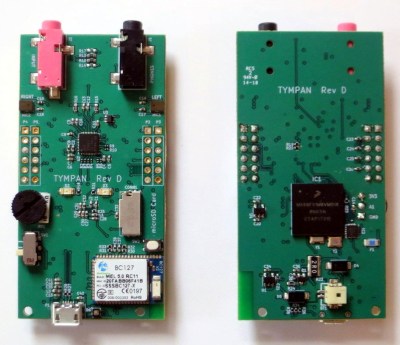

Back when the system was still considered “modern”, [PJ] tried to build a wireless controller using DTMF over FM radio. He couldn’t get it to work exactly right and ended up shelving the project until the present day. Now, we have a lot more tools at our disposal than analog radio, so he pulled out an Arduino and a few Bluetooth modules. There’s a bit of finesse to getting the old hardware to behave with the modern equipment, though, but once [PJ] worked through the kinks he was able to play his classic games like Defender without the limitations of wired controllers.

The Commodore 64 was incredibly popular in the ’80s and early ’90s, and its legacy is still seen today. People are building brand new machines, building emulators for them, or upgrading their hardware.