Although the world of embedded software development languages seem to span somewhere between ASM and C89 all the way to MicroPython, there is a lot to be said for a happy medium between ease of development and features that makes the software more robust without adding overhead or bloat to the final firmware image.

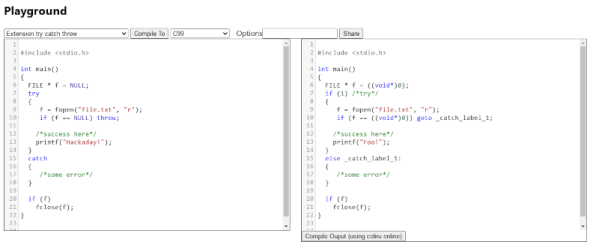

This is where C++ has objectively many advantages over even C99, and as [Çağlayan Dökme] argues in a recent blog post C++17 adds many developer critter comforts to C++98 and the more recent C++11 C++14 standards.

First stepping back a generation (technically two, with C++20 also being a thing already), the addition of binary literals (e.g. 0b1010'1100) in C++14 and the expanded use of constexpr is addressed, with the latter foreshadowing C++17’s increased focus on compile time optimizations. A new attribute in C++17 that is part of this is [[nodiscard]], which when added before to the return type of a function or method requires the return value to be used in some manner, much like with functions in Ada (contrasted with procedures).

As [Çağlayan] notes, the biggest strength of compile-time checks is that it can save a lot of deploy-test-fix round-trips, with the total number of issues caught after deployment that could have been caught during compilation ideally being zero. Here C++17 streamlines the static_assert() mechanism and simplifies using if constexpr to instantiate code depending on compile-time conditions. Beyond compile-time optimizations there are a few other niceties, such as C++17 guaranteeing copy elision (return value optimization) when an object is returned directly, which is a welcome feature in hard real-time environments.

With today even MCUs having enough grunt to run multi-threaded applications and potentially firmware compiled from a many-thousand LoC codebase, picking a programming language that assists the developer with such an arduous task is very important, with Ada being the primary choice for high-reliability embedded platforms, but C++ along with C enjoying the most widespread (free) compiler support. Even if C++ isn’t supported on every single MCU out there (8051-based and most PIC MCUs mostly), whenever it is an option, it’s a pretty solid choice, especially with knowledge of these new language features.