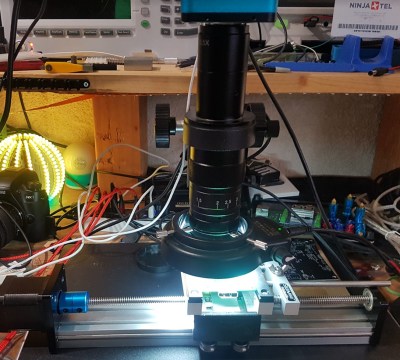

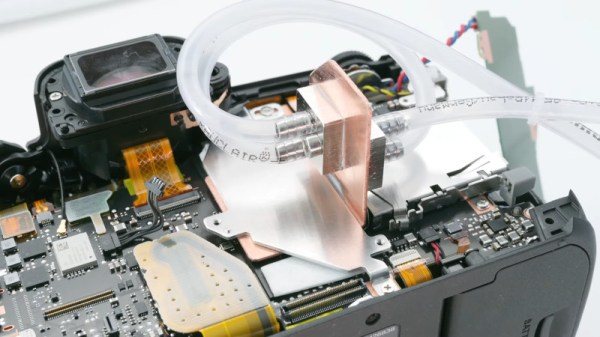

Security cameras are a commodity item these days, but that doesn’t mean [edgett’s] design using a Pi Zero, an Arducam, an LED ring, and active cooling isn’t worth a look. This is a great example of how integrating some off-the-shelf modules and 3D printing can create very professional-looking results. There’s also a trackball interface so you can control the camera. The software, written in Python, is available on GitHub.

The trackball doesn’t move the camera, but it does manage a menu system that lets you capture a photo or video, set the optical parameters like exposure, shutter, and ISO, and launch Camera Remote to offer a Web-based interface instead of the trackball.

If you add infrared illumination, you can swap out the camera for an IR version and have a nice-looking night vision camera, too. The camera is reasonably compact. Not including the lens and the tripod, the camera measures 100 by 44 by 44 mm. So under two inches square and about 4 inches long.

We worried a little about gluing the LED ring down, but then again our phones are all glued together these days, so maybe we should stop fretting. One thing we didn’t see on either site, though, was a picture taken with the camera itself. However, the 12-megapixel camera and quality lens should do a great job. We’ve even seen that particular camera module work with a much smaller computer recently.