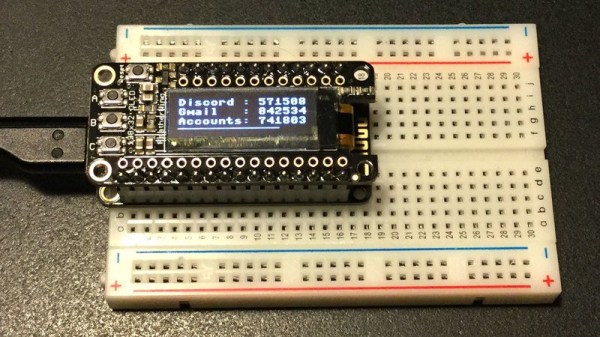

If you’ve ever engaged in social media, you’re familiar with the little thrill you receive when your post, tweet, or project gets a like. But, if logging in feels like too much overhead to obtain your dopamine reward, [pt’s] CircuitPython Hackaday portal may be just what you’re looking for. This project creates a stand-alone counter to display the number of “skulls” (aka likes) received by a project on hackaday.io, and of course, it’s currently counting its own.

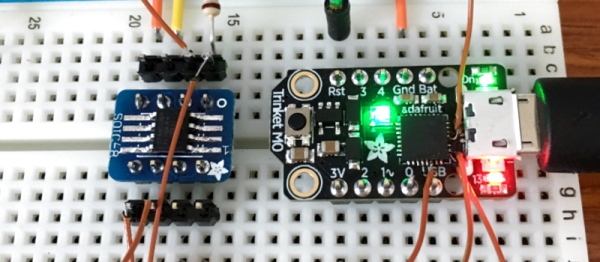

The code is running on a SAMD51 (Cortex M4) microcontroller and serving up the skulls on 240×320 TFT display. For WiFi connectivity, the project uses an ESP-32 controlled through the usual AT command set. All the gory details of this interaction are abstracted away by a CircuitPython library, which is great because that code really isn’t something you want to write for every project. The program accesses the hackaday.io API to retrieve the number of skulls for the project, but could be easily modified to interface with any service that returned a JSON result.

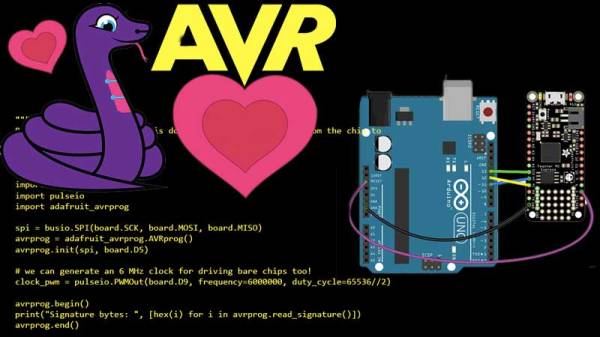

We’ve been seeing a lot of CircuitPython code lately. Just in case you’re not familiar with it, CircuitPython is Adafruit’s version of Micropython, a python language targeted at embedded processors. While it sounds like something concocted purely to make old-school embedded-C programmers grumble, it’s actually powerful and convenient for embedded prototyping and development. Fueled by the speed of the latest inexpensive microcontrollers and a rapidly growing set of libraries that take the sting out of using integrated peripherals and common hacker-friendly parts, it offers a solid alternative to older embedded frameworks. There are lots of examples around if you want to get started, and we’re maintaining our own list of CircuitPython projects over on hackaday.io that you can check out.

You can see a video of the display after the break. It’s not a live stream, so you won’t see your like appear on the display, but rest assured, [pt] will!