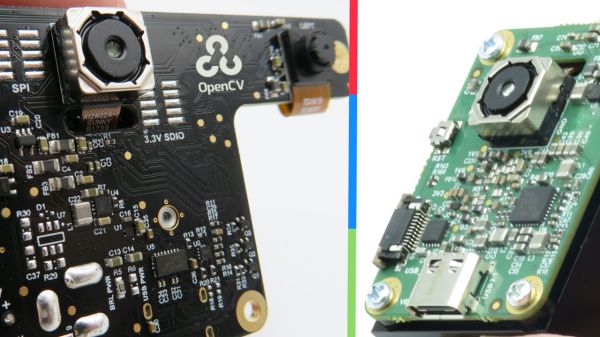

With the Jetson Nano, NVIDIA has done a fantastic job of bringing GPU-accelerated machine learning to the masses. For less than the cost of a used graphics card, you get a turn-key Linux computer that’s ready and able to handle whatever AI code you throw at it. But if you’re trying to set up a lab for 30 students, the cost of even relatively affordable development boards can really add up.

Which is why [Tea Vui Huang] has developed jetson-emulator. This Python library provides a work-alike environment to NVIDIA’s own “Hello AI World” tutorials designed for the Jetson family of devices, with one big difference: you don’t need the actual hardware. In fact, it doesn’t matter what kind of computer you’ve got; with this library, anything that can run Python 3.7.9 or better can take you through NVIDIA’s getting started tutorial.

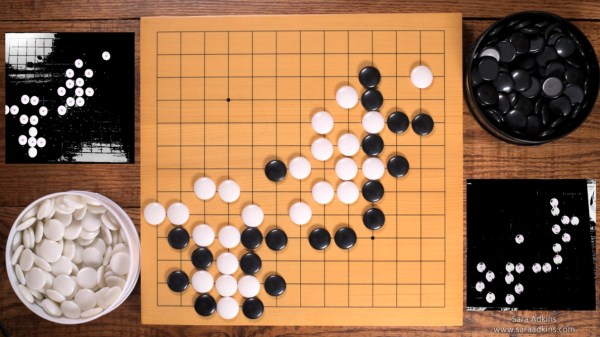

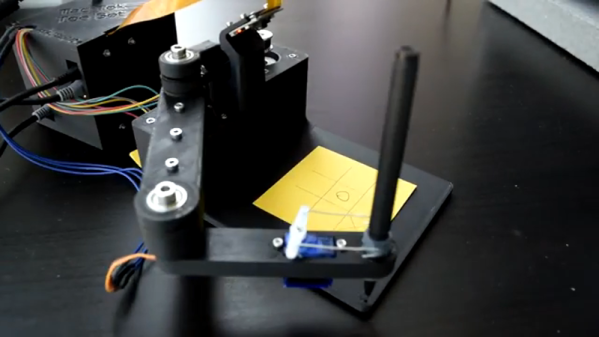

So what’s the trick? Well, if you haven’t guessed already, it’s all fake. Obviously it can’t actually run GPU-accelerated code without a GPU, so the library [Tea] has developed simply pretends. It provides virtual images and even “live” camera feeds to which randomly generated objects have been assigned.

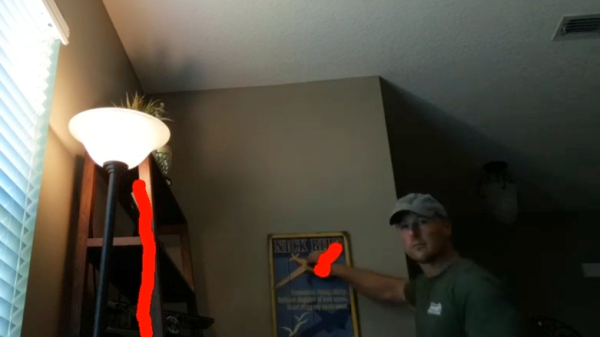

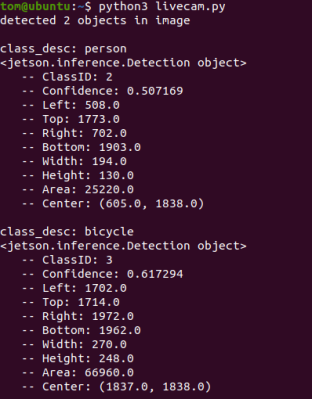

The original NVIDIA functions have been rewritten to work with these feeds, so when you call something like net.Classify(img) against one of them you’ll get a report of what faux objects were detected. The output will look just like it would if you were running on a real Jetson, down to providing fictitious dimensions and positions for the bounding boxes.

If you’re a hacker looking to dive into machine learning and computer vision, you’d be better off getting a $59 Jetson Nano and a webcam. But if you’re putting together a workshop that shows a dozen people the basics of NVIDIA’s AI workflow, jetson-emulator will allow everyone in attendance to run code and get results back regardless of what they’ve got under the hood.