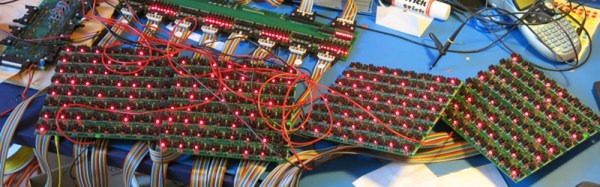

Over 750,000 people pass through New York City’s Grand Central Terminal each day. Located in the heart of the city, it’s one of the largest train stations in the world. Its historic significance dates back to 1913, when it opened its doors to the public. At the time, few were aware of the secret computer that sat deep in a sub basement below the hustle and bustle of the city’s busy travelers. Its existence was kept secret all the way into the 1980’s.

Westinghouse had designed a system that would allow authorities to locate a stuck train in a tunnel. There were cords stretched the length of the tunnels. If a train stalled, the operator could reach out and yank on the cord. This would set off an alarm that would alert everyone of the stuck train. The problem being that even though they knew a train was down, they did not know exactly where. And that’s where the computer come in. Westinghouse designed it to calculate where the train was, and write its location on some ticker tape.

So this is the part of the post where we tell you how the computer established where exactly the train breakdown occurred. Although the storyteller in the video is admirably enthusiastic about telling the story, our depth of detail on the engineering that went into this seems nowhere to be found. Let us know in the comments below if you have a source of more information. Or just post your own conjecture on how you would have done it with the early 20th century tech.

The invention of the two way radio made the whole thing obsolete not long after is was built. Never-the-less, it remains intact to this day.

Thanks to [Greg] for the tip!

![Jef Raskin A Collection of [Jef Raskin]'s work](https://i0.wp.com/hackaday.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/jef-raskin.jpg?w=796&h=353&ssl=1)