Before the Raspberry Pi came out, one cheap and easy way to get GPIO on a computer with a real operating system was to manipulate the pins on an old parallel port, then most commonly used for printers. Luckily, as that port became obsolete we got the Raspberry Pi, which has the GPIO and a number of other advantages over huge desktop computers from the 90s and 00s as well. But if you really miss that form factor or as yearn for the days of the old parallel port, this build which puts a Raspberry Pi into a mini ITX desktop case is just the thing for you.

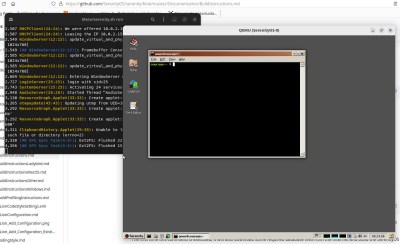

There are a few features that make this build more than just a curiosity. The most obvious is that the Pi actually has support for PCIe and includes a single PCIe x1 slot which could be used for anything from a powerful networking card to an NVMe to a GPU for parallel computing in largely the same way that any desktop computer might them. The Pi Compute Module 5 that this motherboard is designed for doesn’t provide power to the PCIe slots automatically though, but the power supply that can be installed in the case should provide power not only to the CM5 but to any peripherals or expansion cards, PCIe or otherwise, that you could think of to put in this machine.

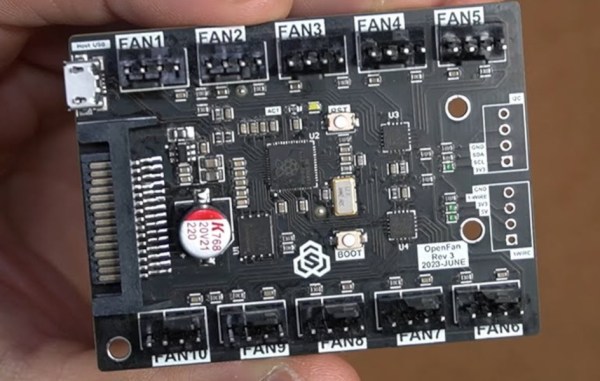

Of course all the GPIO is also made easily accessible, and there are also pins for installing various hats on the motherboard easily as well. And with everything installed in a desktop form factor it also helps to improve the cable management and alleviate the rats-nest-of-wires problems that often come with Pi-based projects. There’s also some more information on the project’s Hackaday.io page. And, if you’re surprised that Raspberry Pis can use normal graphics cards now, make sure to take a look at this build from a few years ago that uses completely standard gaming GPUs on the Pi 5.