A common complaint around modern passenger vehicles is that they are over-reliant on electronics, from overly complex infotainment systems to engines that can’t be fixed on one’s own due to the proprietary computer control systems. But even still, when following the circuits to their ends you’ll still ultimately find a physical piece of hardware. A group of Honda Insight owners are taking advantage of this fact to trick the computers in their cars into higher performance with little more than a handful of resistors.

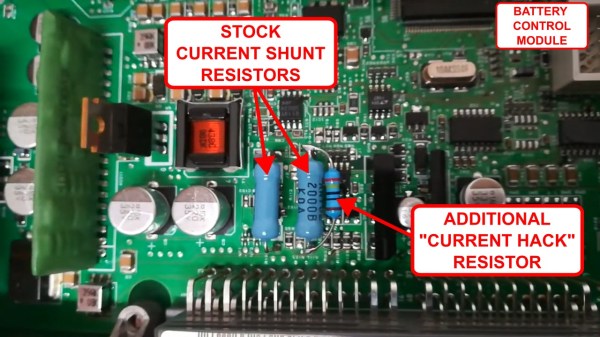

The relatively simple modification to the first-generation Insight involves a shunt resistor, which lets the computer sense the amount of current being drawn from the hybrid battery and delivered to the electric motor. By changing the resistance of this passive component, the computer thinks that the motor is drawing less current and allows more power to be delivered to the drivetrain than originally intended. With the shunt resistor modified, which can be done with either a bypass resistor or a custom circuit board, the only other change is to upgrade the 100 A fuse near the battery for a larger size.

With these two modifications in place, the electric motor gets an additional 40% power boost, which is around five horsepower. But for an electric motor which can output full torque at zero RPM, this is a significant boost especially for a relatively lightweight car that’s often considered under-powered. It’s a relatively easy, inexpensive modification though which means the boost is a good value, although since these older hybrids are getting along in years the next upgrade might be a new traction battery like we’ve seen in the older Priuses.

Thanks to [Aut0l0g1c] for the tip!