Remember the Key Bridge collapse? With as eventful a year as 2025 has been, we wouldn’t blame anyone for forgetting that in March of 2024, container ship MV Dali plowed into the bridge across Baltimore Harbor, turning it into 18,000 tons of scrap metal in about four seconds, while taking the lives of six very unlucky Maryland transportation workers in the process. Now, more than a year and a half after the disaster, we finally have an idea of what caused the accident. According to the National Transportation Safety Board’s report, a loss of electrical power at just the wrong moment resulted in a cascade of failures, leaving the huge vessel without steerage. However, it was the root cause of the power outage that really got us: a wire with an incorrectly applied label.

humanoid robot12 Articles

Chinese Humanoid Robot Establishes New Running Speed Courtesy Of Running Shoes

As natural as walking is to us tail-less bipedal mammals, the fact of the matter is that it took many evolutionary adaptations to make this act of controlled falling forward work (somewhat) reliably. It’s therefore little wonder that replicating bipedal walking (and running) in robotics is taking a while. Recently a Chinese humanoid robot managed to bump up the maximum running speed to 3.6 m/s (12.96 km/h), during a match between two of Robot Era’s STAR1 humanoid robots in the Gobi desert.

For comparison, the footspeed of humans during a marathon is around 20 km/h and significantly higher with a sprint. These humanoid robots did a 34 minute run, with an interesting difference being that one was equipped with running shoes, which helped it reach these faster speeds. Clearly the same reasons which has led humans to start adopting footwear since humankind’s hunter-gatherer days – including increased grip and traction – also apply to humanoid robots.

That said, it looks like the era when humans can no longer outrun humanoid robots is still a long time off.

Continue reading “Chinese Humanoid Robot Establishes New Running Speed Courtesy Of Running Shoes”

Re-imagining Telepresence With Humanoid Robots And VR Headsets

Don’t let the name of the Open-TeleVision project fool you; it’s a framework for improving telepresence and making robotic teleoperation far more intuitive than it otherwise would be. It accomplishes this in part by taking advantage of the remarkable technology packed into modern VR headsets like the Apple Vision Pro and Meta Quest. There are loads of videos on the project page, many of which demonstrate successful teleoperation across vast distances.

Teleoperation of robotic effectors typically takes some getting used to. The camera views are unusual, the limbs don’t move the same way arms do, and intuitive human things like looking around to get a sense of where everything is don’t translate well.

To address this, researches provided a user with a robot-mounted, real-time stereo video stream (through which the user can turn their head and look around normally) as well as mapping arm and hand movements to humanoid robotic counterparts. This provides the feedback to manipulate objects and perform tasks in a much more intuitive way. In short, when our eyes, bodies, and hands look and work more or less the way we expect, it turns out it’s far easier to perform tasks.

The research paper goes into detail about the different systems, but in essence, a stereo depth and RGB camera is perched with a 3D printed gimbal atop a humanoid robot frame like the Unitree H1 equipped with high dexterity hands. A VR headset takes care of displaying a real-time stereoscopic video stream and letting the user look around. Hand tracking for the user is mapped to the dexterous hands and fingers. This lets a person look at, manipulate, and handle things without in-depth training. Perhaps slower and more clumsily than they would like, but in an intuitive way all the same.

Interested in taking a closer look? The GitHub repository has the necessary code, and while most of us will never be mashing ADD TO CART on something like the Unitree H1, the reference design for a stereo camera streaming to a VR headset and mirroring head tracking with a two-motor gimbal looks like the sort of thing that would be useful for a telepresence project or two.

Continue reading “Re-imagining Telepresence With Humanoid Robots And VR Headsets”

Ask Hackaday: What’s The Deal With Humanoid Robots?

When the term ‘robot’ gets tossed around, our minds usually race to the image of a humanoid machine. These robots are a fixture in pop culture, and often held up as some sort of ideal form.

Yet, one might ask, why the fixation? While we are naturally obsessed with recreating robots in our own image, are these bipedal machines the perfect solution we imagine them to be?

Continue reading “Ask Hackaday: What’s The Deal With Humanoid Robots?”

Did You Meet Pepper?

Earlier this week it was widely reported that Softbank’s friendly-faced almost-humanoid Pepper robot was not long for this world, as the Japanese company’s subsidiary in France that had been responsible for the robotic darling of the last decade was being downsized, and that production had paused. Had it gone the way of Sony’s Aibo robotic puppy or Honda’s crouching-astronaut ASIMO? It seems not, because the company soon rolled back a little and was at pains to communicate that reports of Pepper’s untimely death had been greatly exaggerated. It wasn’t so long ago that Pepper was the face of future home robotics, so has the golden future become a little tarnished? Perhaps it’s time to revisit our plastic friend.

A Product Still Looking For A Function

Pepper made its debut back in 2014, a diminutive and child-like robot with basic speech recognition and conversation skills, the ability to recognize some facial expressions, and a voice to match those big manga-style eyes. It was a robot built for personal interaction rather than work, as those soft tactile hands are better suited to a handshake than holding a tool. It found its way into Softbank stores as well as a variety of other retail environments, it was also used in experiments to assess whether it could work as a companion robot in medical settings, and it even made an appearance as a cheerleading squad. It didn’t matter that it was found to be riddled with insecurities, it very soon became a favourite with media tech pundits, but it remained at heart a product that was seeking a purpose rather than one ready-made to fit a particular function.

I first encountered a Pepper in 2016, at the UK’s National Museum of Computing. It was simply an exhibit under the watchful eye of a museum volunteer rather than being used to perform a job, and it shared an extremely busy gallery with an exhibit of Acorn classroom computers from the 1980s and early ’90s. It was an odd mix of the unexpected and the frustrating, as it definitely saw me and let me shake its hand but stubbornly refused to engage in conversation. Perhaps it was taking its performance as a human child seriously and being shy, but the overwhelming impression was of something that wasn’t ready for anything more than experimental interaction except via its touch screen. As a striking contrast in 2016 the UK saw the first release of the Amazon Echo, a disembodied voice assistant that might not have had a cute face but which could immediately have meaningful interactions with its owner.

How Can A Humanoid Robot Compete With A Disembodied Voice?

In comparing the Pepper with an Amazon Echo it’s possible that we’ve arrived at the root of the problem. Something that looks cool is all very well, but without immediate functionality, it will never capture the hearts of customers. Alexa brought with it the immense power of Amazon’s cloud computing infrastructure, while Pepper had to make do with whatever it had on board. It didn’t matter to potential customers that a cloud-connected microphone presents a huge privacy issue, for them a much cheaper device the size of a hockey puck would always win the day if it could unfailingly tell them the evening’s TV schedule or remind them about Aunty’s birthday.

Over the next decade we will see the arrival of affordable and compact processing power that can do more of the work for which Amazon currently use the cloud. Maybe Pepper will never fully receive that particular upgrade, but it’s certain that if Softbank don’t do it then somebody else will. Meanwhile there’s a reminder from another French company that being first and being cute in the home assistant market is hardly a guarantee of success, who remembers the Nabaztag?

Header: Tokumeigakarinoaoshima, CC0.

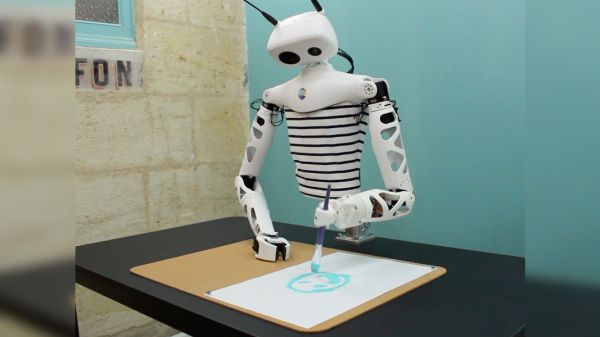

Reachy The Open Source Robot Says Bonjour

Humanoid robots always attract attention, but anyone who tries to build one quickly learns respect for a form factor we take for granted because we were born with it. Pollen Robotics wants to help move the field forward with Reachy: a robot platform available both as a product and as a wealth of information shared online.

This French team has released open source robots before. We’ve looked at their Poppy robot and see a strong family resemblance with Reachy. Poppy was a very ambitious design with both arms and legs, but it could only ever walk with assistance. In contrast Reachy focuses on just the upper body. One of the most interesting innovations is found in Reachy’s neck, a cleverly designed 3 DOF mechanism they called Orbita. Combined with two moving antennae at the top of the head, Reachy can emote a wide range of expressions despite not having much of a face. The remainder of Reachy’s joints are articulated with Dynamixel serial bus servos though we see an optional Orbita-based hand attachment in the demo video (embedded below).

Reachy’s € 19,990 price tag may be affordable relative to industrial robots, but it’s pretty steep for the home hacker. No need to fret, those of us with smaller bank accounts can still join the fun because Pollen Robotics has open sourced a lot of Reachy details. Digging into this information, we see Reachy has a Google Coral for accelerating TensorFlow and a Raspberry Pi 4 for general computation. Mechanical designs are released via web-based Onshape CAD. Reachy’s software suite on GitHub is primarily focused on Python, which allows us to experiment within a Jupyter notebook. Simulation can be done within Unity 3D game engine, which can be optionally compiled to run in a browser like the simulation playground. But academic robotics researchers are not excluded from the fun, as ROS1 integration is also available though ROS2 support is still on the to-do list.

Reachy might not be as sophisticated as some humanoid designs we’ve seen, and without a lower body there’s no way for it to dance. But we are very appreciative of a company willing to share knowledge with the world. May it spark new ideas for the future.

[via Engadget]

Continue reading “Reachy The Open Source Robot Says Bonjour”

Robotic Biped Walks On Inverse Kinematics

Robotics projects are always a favorite for hackers. Being able to almost literally bring your project to life evokes a special kind of joy that really drives our wildest imaginations. We imagine this is one of the inspirations for the boom in interactive technologies that are flooding the market these days. Well, [Technovation] had the same thought and decided to build a fully articulated robotic biped.

Each leg has pivot points at the foot, knee, and hip, mimicking the articulation of the human leg. To control the robot’s movements, [Technovation] uses inverse kinematics, a method of calculating join movements rather than explicitly programming them. The user inputs the end coordinates of each foot, as opposed to each individual joint angle, and a special function outputs the joint angles necessary to reach each end coordinate. This part of the software is well commented and worth your time to dig into.

In case you want to change the height of the robot or its stride length, [Technovation] provides a few global constants in the firmware that will automatically adjust the calculations to fit the new robot’s dimensions. Of all the various aspects of this project, the detailed write-up impressed us the most. The robot was designed in Fusion 360 and the parts were 3D printed allowing for maximum design flexibility for the next hacker.

Maybe [Technovation’s] biped will help resurrect the social robot craze. Until then, happy hacking.

Continue reading “Robotic Biped Walks On Inverse Kinematics”