We see a lot of discrete-logic computer builds these days, and we love them all. But after a while, they kind of all blend in with each other. So what’s the discrete logic aficionado to do if they want to stand out from the pack? Perhaps this CPU-less computer with a single NOR-gate instead of an arithmetic-logic unit is enough of a hacker flex? We certainly think so.

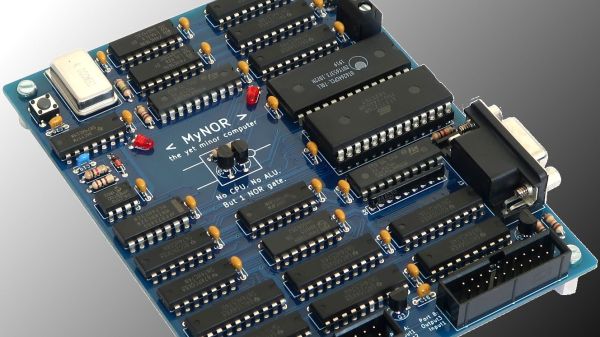

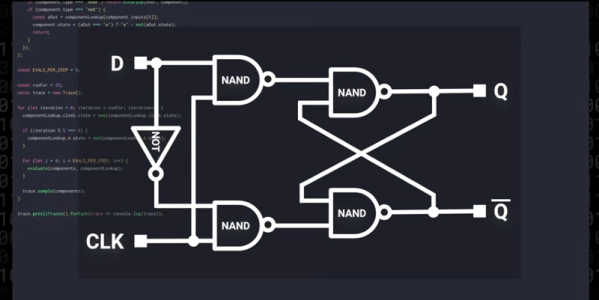

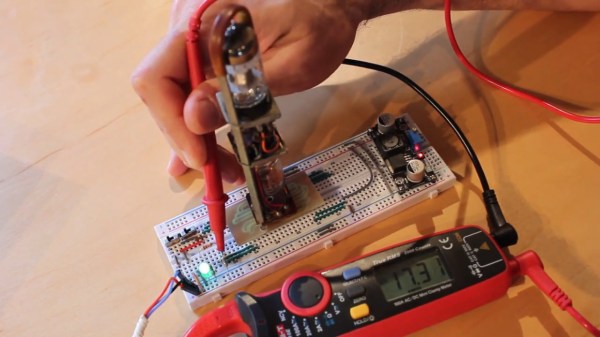

We must admit that when we first saw [Dennis Kuschel]’s “MyNor” we thought all the logic would be emulated by discrete NOR gates, which of course can be wired up in various combinations to produce every other logic gate. And while that would be really cool, [Dennis] chose another path. Sitting in the middle of the very nicely designed PCB is a small outcropping, a pair of discrete transistors and a single resistor. These form the NOR gate that is used, along with MyNor’s microcode, to perform all the operations normally done by the ALU.

While making the MyNor very slow, this has the advantage of not needing 74-series chips that are no longer manufactured, like the 74LS181 ALU. It may be slow, but as seen in the video below, with the help of a couple of add-on cards of similar architecture, it still manages to play Minesweeper and Tetris and acts as a decent calculator.

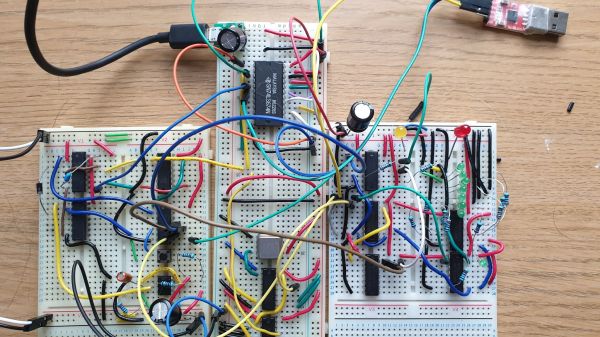

We really like the look of this build, and we congratulate [Dennis] on pulling it off. He has open-sourced everything, so feel free to build your own. Or, check out some of the other CPU-less computers we’ve featured: there’s the Gigatron, the Dis-Integrated 6502, or the jumper-wire jungle of this 8-bit CPU-less machine.

Continue reading “A CPU-Less Computer With A Single NOR-Gate ALU”