Unless you’re running a commercial logging operation, with specialized saws, log grapples, mills, transportation for the timber, and the skilled workers needed to run everything, it’s generally easier to bring a sawmill to the wood instead of taking the wood to the sawmill. Especially for a single person, something like a chainsaw mill is generally a much easier and cost effective way to harvest a small batch of timber into lumber. These chainsaw mills can still be fairly cumbersome though, but [izzy swan] has a new design that fits an entire mill onto a hand cart for easy transportation in and out of a forest.

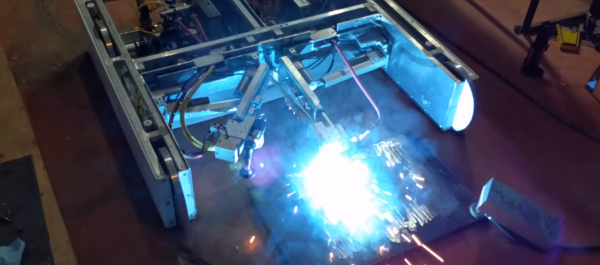

The entire mill is built out of a sheet and a half of plywood, most of which is cut into strips and then assembled into box girders for the track. The remainder of plywood is machined on a CNC to create the carriage for the chainsaw to attach as well as a few other parts to fix the log in place. The carriage has a 4:1 reduction gear on it to winch the chainsaw along the length of the log which cuts the log into long boards. After the milling is complete, the entire mill can be disassembled and packed down onto its hand cart where it can be moved on to the next project fairly quickly.

For a portable mill, it boasts respectable performance as well. It can cut logs up to 11 feet in length and about 30 inches across depending on the type of chainsaw bar used, although [izzy swan] has a few improvements planned for the next prototypes that look to make more consistent, uniform cuts. Chainsaws are incredibly versatile tools to have on hand as well, we’ve seen them configured into chop saws, mortisers, and even fixed to the end of a CNC machine.

Thanks to [Keith] for the tip!