[Larry Wall], inventor of Perl, once famously said that programmers have three key virtues: sloth, hubris, and impatience. It’s safe to say that these personality quirks are also present in some measure in most hardware hackers, too, with impatience being perhaps the prime driver of great hacks. Life’s too short to wait for someone else to build it, whatever it may be.

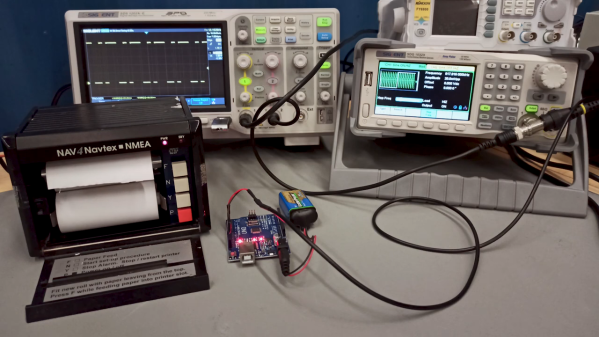

Impatience certainly came into play for [Sebastian (AI5GW)] while hacking a NAVTEX receiver (in German). The NAVTEX system allows ships at sea to receive text broadcast alerts for things like changes in the weather or hazards to navigation. The trouble is, each NAVTEX station only transmits once every four hours, making tests of the teleprinter impractical. So [Sebastian]’s solution was to essentially create his own NAVTEX transmitter.

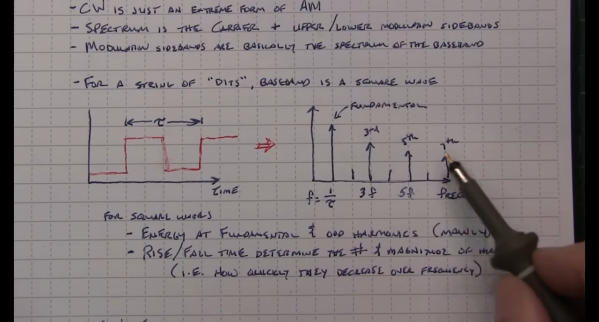

Job one was to understand the NAVTEX protocol, which is a 100-baud, FSK-modulated signal with characters encoded in CCIR 476. Since this encoding is also used in amateur radio teletype operations, [Sebastian] figured there would surely be an Arduino library for encoding and decoding it. Surprisingly, there wasn’t, but there is now, allowing an Arduino to produce the correct sequence of pulses for a CCIR 476-encoded message. Fed into a function generator, the mini-NAVTEX station’s signal was easily received and recorded by the painfully slow teleprinter. There’s that impatience again.

We thought this was a neat hack, and we especially appreciate that [Sebastian]’s efforts resulted in a library that could be useful to hams and other radio enthusiasts in the future. We’ve talked about some more modern amateur radio digital modes, like WSPR and FT8, but maybe it’s time to look at some other modes, too.

Continue reading “Impatience Is A Virtue When Testing This Old Maritime Teleprinter” →